The importance of children's and household tales

Dr. Stefan Neumann / German Studies

Photo: UniService Transfer

When evil loses, we feel good

An interview with Dr. Stefan Neumann about the significance of the Brothers Grimm's fairy tales Mr. Neumann, generations of children have grown up with Grimm's fairy tales. What is the situation today? Do fairy tales still work in the age of digitalization?

Neumann: I would say better than ever. Digital content is largely based on fairy tales. Many games and stories for children that are conveyed digitally adopt plots and basic structures from fairy tales. So you could say that digital storytelling wouldn't work without fairy tales.

On the other hand, a look at the classic fairy tale shows that it contains much of what we lack in our digitalized world: fairy tales educate their listeners or readers to independence, including individuality. Fairy tales celebrate the outsiders: Cinderella, the little brother that nobody would bet on or the poor, abandoned child. These are all individuals who wouldn't pass as influencers, but make their fortune in the end, despite their difficult situation. They manage to conquer their world and master their lives through decisions that rarely follow the mainstream. The digital world, at least in the form in which it appears today, especially where children are on the move, i.e. in social media, tends to educate them to certain views or worldviews that are dictated by the mainstream or by marketing. Fairy tales give outsiders a chance.

In a list of the 10 cruelest Grimm's fairy tales, Snow White is in 8th place. Fairy tales weren't actually originally intended for children, were they?

Neumann: You could say that, but what we understand as childhood today hasn't been around that long. Before the 18th century, before the Enlightenment, there was virtually no literature specifically for children. This has to do with the fact that childhood was not a protected space, as it has developed since then. We give children time to grow up, learn and play. That didn't exist back then: children were more like unfinished adults who ran along, had to work within the limits of their strength and also sat around telling each other fairy tales in the evening after work. There was no children's literature at all. In this respect, they were not made for children, but children knew fairy tales even before the Grimms.

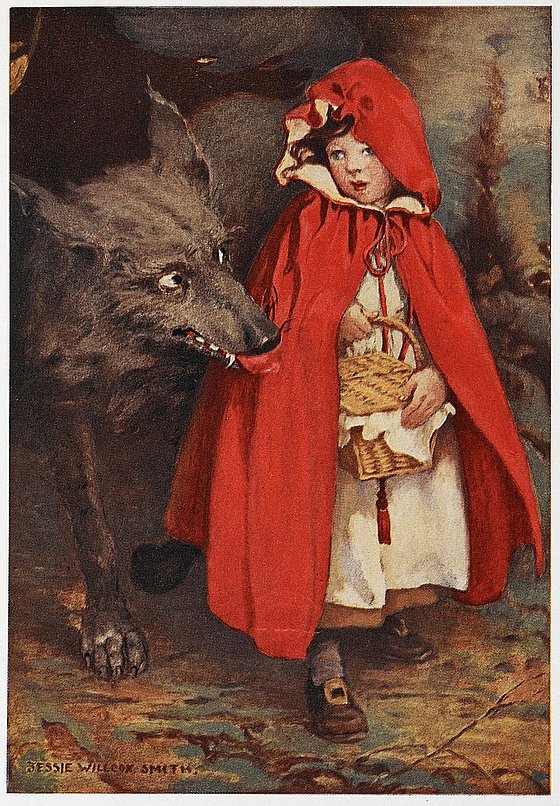

Little Red Riding Hood

Jessie Wilcox Smith, public domain

The interplay between good and evil is often dealt with in Grimm's fairy tales, with good always winning out. "The fairy tale is the only poetic form in which evil disappears at the end. And forever, without return," says fairy tale researcher Kristina Wardetzky from Berlin. Why is that so important and right?

Neumann: It's important because we don't want to be afraid when we go to bed after a bedtime story. There must be no danger that evil could come back at night and harm us. That is also the reason why evil must be destroyed. It must have no chance of harming me as a listener after the fairy tale is over. And ultimately that's also the case in every blockbuster. We want a good ending, we want evil to lose. That's in our nature, and if we get that, then we feel good.

How did the Brothers Grimm actually come up with all these stories?

Neumann: A whole seminar could be held on this. Prof. Heinz Rölleke, the so-called fairy tale pope, who was a literary scholar here at the university until 2001, did a lot of research into this. The Grimms had oral sources, but also searched for fairy tales in old books and folios. They advertised in magazines that they were looking for fairy tales and that people should please send them some if they knew of any. The distribution of oral and written sources was about 50/50. This was also a suitable time during the Romantic period, because Napoleon's occupation of Germany had dissolved all the monasteries and the libraries were cheap to buy. This meant that old books that didn't cost a fortune were available. The two brothers did the same as young students. In the case of oral sources, they first went out and asked older people about fairy tales. However, this was not very successful, as the two were also very shy. In the end, the Grimms had most of the fairy tales told to them by their acquaintances, with whom they regularly met as students in a kind of literary circle. These were mainly educated young women. They told many of the fairy tales that we find in the collection. This is very interesting because they were storytellers and therefore the female perspective can also be found in the fairy tales. Many of these women came from the Hessian educated middle classes and had French roots; they were descendants of Huguenots who had settled in Hesse. As a result, many of the stories in the Grimm collection were of French origin. Even though people often talk about German folk tales, the brothers themselves never did. They did write a German grammar and a German book of legends, but the fairy tale book is called 'Kinder- und Hausmärchen' because they had already guessed that many fairy tales did not originally come from Germany, but from all over Europe.

The wolf and the seven little goats,

Illustration by Heinrich Leutemann, Carl Offterdinger, public domain

In 1947, the British lieutenant T. J. Leonard examined the schoolbooks of the Wilhelmine era and came to the conclusion that the Grimm fairy tales had a devastating influence on German children and created in them an unconscious tendency towards cruelty. Can we still accept that today?

Neumann: It is understandable that someone would look for a reason for the absolutely barbaric outbreak of an actually cultivated people in view of all the deaths in the Second World War. However, blaming it on fairy tales is absolutely nonsensical. Fairy tales are actually texts that primarily spread optimism and emancipation from those on whom one is dependent. In this respect, I would describe fairy tales as fundamentally positive. At the same time, fairy tales are very open texts that contain a lot of blank spaces that can be interpreted and interpreted for oneself. In a certain sense, this makes fairy tales susceptible to abuse. If you look around the market for fairy tale interpretations, there are incredible interpretations that have nothing whatsoever to do with the actual text. A lot of esotericism, for example. And the Nazis misused fairy tales in exactly the same way. They interpreted the fairytale hero or heroes as loyal, open Germans who are betrayed and threatened by other peoples, represented by witches, wizards and evil kings, but who ultimately triumph. And of course this can also be found in Wilhelmine and National Socialist textbooks. Many fairy tales are of French, Dutch or Scottish origin. So there is no such thing as a German fairy tale, but rather European folk tales.

In his book "Children need fairy tales", psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim writes about the importance and necessity of fairy tales for adolescents. Other voices insist that fairy tales are simply too cruel for children and show outdated role models. How does society deal with this?

Neumann: In his book, Bruno Bettelheim gets to the heart of the importance of fairy tales for children, even if he is no longer quite up to date with his Freudian methodology. But it is true that fairy tales help children to get through conflicts, tackle problems and remain optimistic. In current resilience research, i.e. research into how people get through and overcome crises, fairy tales play a prominent role. And depriving children of cruelty in fiction has proven to be a mistake. After all, children are also confronted with cruelty in real life. Fairy tales prepare them for this and show them how to get out of it. The message is: don't give up, don't lose hope, act on your own in an emergency and don't wait for help. First the promise in the fairy tale of Rumpelstiltskin: 'I'll spin you straw into gold', but then the demand for something in return, in this case the demand for the first-born child that he is known to want to slaughter and eat. This is again the greatest possible threat to life, which is important to tell an exciting story. Then the newly-born queen has to take action herself. And it's the same with Hansel and Gretel. She first saves the witch from starvation, but then the witch wants to eat her herself, and for children this is again the threat that fairy tales work with. The cruelty in fairy tales is vivid. The cruelty that we imagine when we are told fairy tales can only ever be based on our own experience of cruelty. But of course there are also fairy tales that I would never read to a child today. This certainly includes 'King Thrushbeard'. A princess who doesn't want to get married is humiliated until she settles for a strange-looking aggressive guy, which certainly doesn't fit in with modern times. That's why you should look at fairy tales before you read or tell them.

And today, are there any new fairy tales?

Neumann: Yes, but certainly not folk tales. They can no longer exist in this form in a society that communicates primarily through writing. They belong to a different era. That was also the reason why the Grimms started collecting them, because they were sure that this oral tradition would be lost in 20 or 30 years. In other societies where written culture has not permeated society as a whole, folk tales certainly still exist. But these societies are becoming fewer and fewer. There are, of course, many new fairy tales written by authors. Fairy tale parodies never seem to go out of fashion either.

Finally, is it better to read fairy tales aloud or tell them?

Neumann: From a reading didactic perspective, I would say read aloud. It shows children that books can contain great things and makes them want to read. As a fairy tale didactician, I would say that if you find reading aloud difficult, tell the fairy tales from memory. The most important thing anyway is that there is someone to talk to about what you have heard. That's why personal reading or storytelling is always a benefit for children.

Uwe Blass

Dr. Stefan Neumann works in the Department of Didactics of German Language and Literature in the Faculty of Humanities and Cultural Studies at the University of Wuppertal.