The vertical housing estate

Prof. Dr Christoph Grafe / History and Theory of Architecture

Photo: UniService Third Mission

The vertical housing estate

Christoph Grafe on modern building concepts by the architect Le Corbusier

He was undoubtedly a central figure in modern architecture and urban planning in the 20th century: Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, better known as Le Corbusier (1887 - 1965). The Swiss-French architect presented new approaches to European urban planning at the 1925 International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Art in Paris, visions that could not be realised in the social housing of the post-war period. Christoph Grafe, an architect specialising in the history and theory of architecture, knows his ideas and the reasons for their failure in planning and realisation on a human scale.

Unité d'habitation - the housing unit

The Unité d'habitation, also known as the ”housing machine”, was an idea of Le Corbusier's that he presented at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1925. ”Le Corbusier had actually formulated the concept of 'La machine à habiter', i.e., the housing machine, back in the 1920s,” Grafe explains. ”So what was then realised for the first time in Marseille was therefore part of a much longer process in which he presented a concept for stacked, i.e., vertical, residential construction. This has also been historically examined and documented by now. He actually reworked certain concepts of housing, including spatial concepts, in such a way that they became possible for serial housing construction.” The architect explains that Le Corbusier had already created famous villas during this period, which should be seen as demonstration objects. ”So, he didn't just build a house, but always understood this house as an idea about living and used this idea for architecture. In this case, the five points of architecture (mullions, roof gardens, free floor plan, long windows, and the façade design, editor's note), which are associated with the Villa Savoye (the Villa Savoye is considered an iconic modernist building near Paris, editor's note), are well-known.” Some things can be discovered again and again in his work. One key aspect is a living space that is more than one storey high. ”Many of the villas always have a hall that extends over more than one floor. This idea of space that varies in height is actually a constant in all his concepts for living. The interesting thing is that with the concept of the unité d'habitation, of which there is also a replica in the Musée des Monuments français in Paris, where you can actually walk around in a prototype, he tries to transfer an idea that comes from villa construction and studio buildings to mass housing construction. He realised this idea in Marseille after the Second World War, whereby his wish was that the whole building should be a prototype for other large housing projects throughout France.” Although there are still other complexes of his buildings today, they have not been realised nationwide.

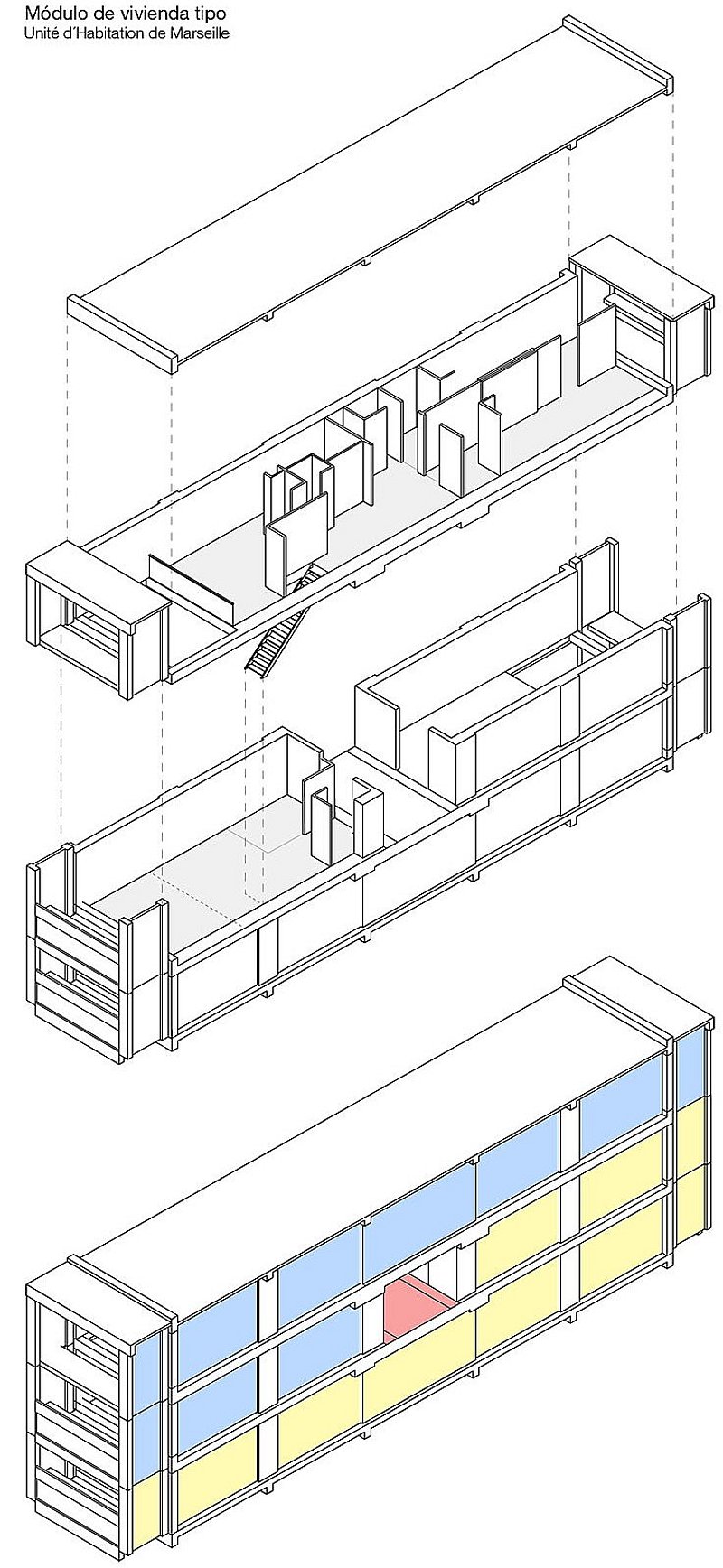

Alberto C. González: Modular structure of the flats in Marseille

Photo: CC BY-SA 4.0

Building principle reminiscent of a bottle rack

The unité d'habitation (housing unit) was designed to offer increased living comfort. In expert circles, the building principle is known as the 'bottle rack'. “This has to do with a schematic representation that Le Corbusier himself produced. He shows his flat as a kind of container of walls that can be pushed into a skeleton in its entirety. It actually looks like a bottle rack into which the floors are pushed, so to speak,” Grafe explains. In reality, it was constructed differently, but it is a completely neutral skeleton construction that is precisely aligned in its dimensions.

Inside the residential complex in Marseille, Photo: CC BY-SA 3.0

The vertical city

“Le Corbusier was sharply opposed to the traditional city, especially that of Parisian prefect Georges-Eugène Haussmann,” Grafe says. He criticised the spaces, the streets and, even back then, the lack of greenery in the city. “He countered this with a city that grows upwards. But this also includes the open field in which the buildings stand as far as possible. These two things are linked. The area should actually remain as open as possible, become a park, the buildings should go up so that living no longer takes place directly on the ground. This means that all buildings are always a city in themselves. In the case of the unité d'habitation, we also have an inner street in the building, which is intended to simulate a piece of the city.”

Unité d'Habitation Marseille,

Photo: CC BY-SA 4.0

The first housing unit was built in Marseille in 1947

The idea of the vertical city was first realised in Marseille in 1947, 22 years after the World Exhibition in Paris. Grafe explains that this construction had to do with the circumstances, as there was a dramatic urgency to create living space after the Second World War. The fact that Le Corbusier, like other well-known architects, had pandered to the Vichy government in power at the time in order to realise his ideas for a new city on a larger scale remains a dark point in his success story. The building in Marseille was gigantic in scale. There were residential units coupled with shops, a hotel and a kindergarten. ”To this day, it is a highly efficient layout that is geared towards a small middle-class family. You can actually live there with a maximum of four people; the flats are basically all the same size. There is one standard unit, which actually consists of this living space, into which a balcony extends from the upper floor. The bedrooms are very narrow, just enough for a double bed. Everything is precisely dimensioned, planned for maximum efficiency, right down to the ceiling height.” Le Corbusier worked with a measuring system he developed, known as the Modulor. This system was based on a human height of 1.83 metres and deviated from the standard heights of house construction. The aspect of the living machine was also evident in the furnishings of the flats. ”There were kitchens, for example, in which the functional sequences were decisive, in which the action sequences could be carried out efficiently,” Grafe says, ”the aspect of the machine becomes very clear there once again. You want to set everything up exactly so that it works.”

Corbusierhaus Berlin,

Photo: CC BY-SA 4.0

Le Corbusier's only residential building outside France is in Berlin

Le Corbusier's idea of the Unité d'habitation was also realised a few years later: the Unité d’habitation Berlin. However, the architect was not happy with the result and even distanced himself from the project. ”This behaviour had to do with the development process. One key aspect was that the Modulor was not realised, but the Berlin building regulations applied. His concept of dimensions and proportions was therefore not followed,” Grafe explains. There were also communication problems. ”Nevertheless, it has to be said that it is the only Unité that was realised outside France. It must be stated that Le Corbusier could not accept that control over the realisation of his idea was taken away from him. You can also see these differences in the design of the Berlin building, it is not as refined, not as artistically high-quality as its French counterparts.”

Le Corbusier 1964 in the Stedelijk Museum,

Photo: CC0

The unité d'habitation remains an interesting concept of living

In the meantime, 17 of Le Corbusier's buildings in various countries were declared UNESCO World Heritage. The new type of unité d'habitation is still controversial today because it was realised independently of local conditions. There is also talk of the 'irrelevance of the location for the architectural decision'. It was a building without 'concession to the respective context'. ”The guidelines have certainly become stricter today,” Grafe says, ”the way we are building at the moment, a clear view of a single person is actually impossible. I myself am an advocate of site-specific construction. Nevertheless, I would say that in almost all temperate climate zones to date, the Unité still offers an interesting concept of living in certain places. If you are in a Unité flat in Marseille, for example, you have a wonderful view of the Mediterranean landscape. And in Briey-en-Forêt, you have a view of the forest and in Nantes you have the western French countryside. You have a living experience that is always site-specific.”

After the Second World War, the concepts of Le Corbusier and other architects were often realised in a watered-down form on a large-scale during reconstruction, the expert explains. ”The watered-down form consists, among other things, in the fact that the generous facilities, such as a restaurant, a hotel or a day-care centre, are usually not implemented, so that the entire community area is actually omitted. This also has to do with the fact that Le Corbusier's concept was not intended for workers' housing. He planned the building, the vertical city, for the well-educated middle class. As a rule, these are people who also go to the restaurant, the hotel and cultivate a public lifestyle. From today's perspective, Grafe concludes, the fact that Le Corbusier's residential units were not realised across the board was a good decision. But the properties that were realised are impressive due to their uniqueness.

In this context, the master's gravestone is also interesting. His name and that of his wife can be read on rectangular stones, stacked vertically and set in a concrete frame.

Uwe Blass

Prof Dr Christoph Grafe has held the Chair of Architecture, History and Theory at the University of Wuppertal since 2013 and has been Dean of the School of Architecture and Civil Engineering since 2024.