Prof Dr Katharina Rennhak / English Studies

Photo: Auen60 Photography

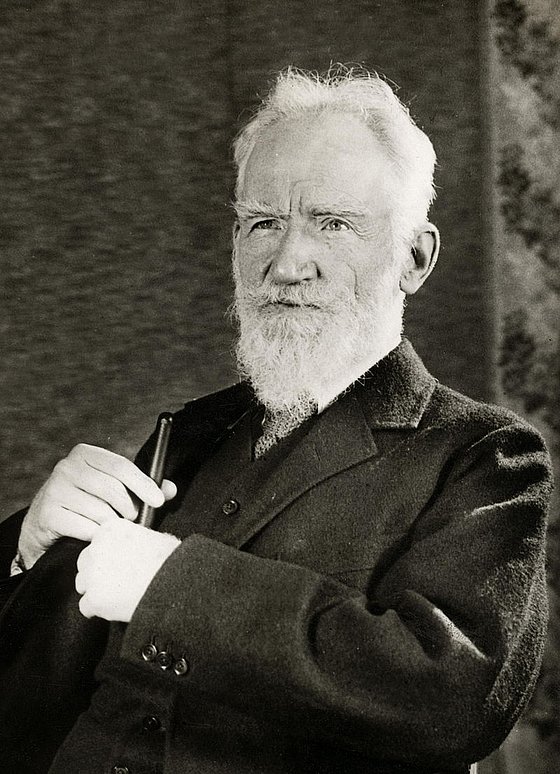

Nobel Prize for Literature for George Bernard Shaw

Prof Dr Katharina Rennhak on the Irish playwright who reformed the world with his dramas

George Bernard Shaw once said: "High education can be proved by knowing how to explain the most complicated things in a simple way." Did he achieve this in his works?

Katharina Rennhak: Yes, that's a typical Shaw saying that is often quoted - and not just in the English-speaking world. We also like to use it to motivate our student teachers. You need a high level of education not only to grasp complicated issues yourself, but also to be able to explain them to others. George Bernard Shaw was not a philosopher himself and did not enrich the world with his own innovative theories. But he studied the great social philosophers and natural scientists of his time, read Marx and Nietzsche, for example, and was fascinated by the theory of evolution, as well as analysing the ideas of Thomas Carlyle and John Stuart Mill. On this basis and very familiar with the modern theatre stage, Shaw transformed the British theatre at the end of the 19th century into a place of enlightenment. His dramas of ideas and debate not only seek to explain the world, but also to reform it politically. This was very much in the spirit of the Fabian Society, a socialist association of bourgeois intellectuals, which Shaw joined and which - unlike Marx - wanted to reform the capitalist system from within. Shaw's aim was to expose social ills and hypocrisies and to encourage his audience to critically scrutinise traditional values and morals. He makes abstract ideas tangible and vivid by bringing believable characters onto the stage and entangling them in an exciting plot. His characters are repeatedly given the opportunity to 'discuss' complicated political and moral issues - relating to religion, class and gender equality and sexuality - in often witty and always entertaining dialogues in front of the audience using pointed everyday language. In short, yes! George Bernard Shaw has honoured what he says about "high education" in his own works.

He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1925. The Nobel Prize Committee wrote that his work was "characterised by both idealism and humanity, its fresh satire often combined with a peculiar poetic beauty". He revolutionised the theatre with his comedic drama and his socially critical plays. He broke taboos and challenged conventions. Can you give an example that illustrates his extraordinary work?

Katharina Rennhak: Yes, the Nobel Prize committee really sums up what characterises George Bernard Shaw's plays. I would like to try to illustrate this with a specific example, namely Mrs Warren's Profession. Shaw dares to tackle the highly sensitive subject of prostitution and treats it neither voyeuristically nor moralistically, but in a socially critical way. The title heroine, Kitty Warren, is a woman who chooses a socially ostracised survival strategy out of extreme economic hardship. Viewers hear the story of Kitty's past almost simultaneously with her daughter Vivie, who only gets to know her mother late in life. It is touching when Kitty talks about her past and makes it clear that single women often simply have no other option. Typically, however, Shaw does not turn such a moment of revelation and a life story characterised by poverty and suffering into a sentimental one. Unlike many of her literary predecessors in the Victorian novel and drama, Kitty Warren is not a repentant, desperate and doomed poor sinner, but a thoroughly self-confident woman. As it turns out later, she now runs a very successful chain of brothels and has amassed quite a bit of wealth. If you like, you can see Shaw's humanism paired with a satirical twist here: The victim of the capitalist-patriarchal system not only saves herself by playing by its rules, but ends up becoming a driving force of that very system herself. In Mrs Warren's Profession , prostitution also proves to be a business from which many (therefore always only seemingly) respectable citizens profit without ever being able to openly admit it. Prostitution thus appears not as the profession of 'fallen women', but as a structural problem. Vivie, the actual heroine of the play, an embodiment of the 'new woman' ideal, ultimately decides against all bourgeois-capitalist economic models open to women around 1900. She neither wants to profit from the wealth of her mother, who is now part of the hypocritical establishment herself, nor does she want to enter into a bourgeois marriage - whether for love or for financial security. Instead, the young woman with a degree in maths from Cambridge University insists on her absolute economic and emotional independence and integrity. Shaw's language, especially in moments where harsh realities and brutal truths are spoken, is not only trenchant and witty, but also poetically powerful due to the emotional authenticity it conveys.

Shaw initially refused the prize money, saying: "I can forgive Alfred Nobel for inventing dynamite, but only a devil in human form could have come up with the idea of inventing the Nobel Prize." What bothered him so much?

Katharina Rennhak: Yes, that's also typical of Shaw. You can see again how he gets to the heart of quite complex problem constellations in a wonderfully concise and brutal way. His rejection of the Nobel Prize was an expression of his scepticism towards any entanglement of capital, art and morality. Ultimately, Shaw says that he finds it forgivable if someone earns money with an invention that not only has positive effects, but can also be used for violence and war. It becomes problematic when a fortune amassed in this way is used to set up foundations with no vested interests. Shaw's comment is primarily aimed at the moral contradiction between the arms trade and an international prize, which - according to the definition of the Nobel Prize - honours those "who have done the greatest service to humanity in the past year". On the one hand, Shaw believes it is simply dishonest for industrialists and entrepreneurs, whose business practices are based solely on the laws of the market and not on moral criteria, to stylise themselves as benefactors by setting up a charitable foundation. Conversely, as a socialist, he did not want to accept money for his artistic work that came from an industrial fortune. Thinking more fundamentally, he feared that artists, scientists and peacemakers were in danger of being bought by institutions such as the Nobel Prize and thus losing their independence and integrity. Interestingly, however, Shaw's reaction to the awarding of the prize also shows what a complex constellation of problems we are dealing with here and how much Shaw must have wrestled with himself when it came to the Nobel Prize: After initially rejecting the Nobel Prize outright, he finally accepted the honour and only refused the prize money. As an artist with moral and political aspirations, he obviously did not want to forgo the broad impact that this institutional recognition would have given him.

He is the only writer to have won both a Nobel Prize and an Oscar. What did he get it for?

Katharina Rennhak: For a very long time, George Bernard Shaw was actually the only person to win both the Nobel Prize for Literature and an Oscar. the Nobel Prize for Literature and an Oscar has won. In 2016, Bob Dylan also received this honour. Shaw won the Oscar in 1939 in the 'Best Adapted Screenplay' category. He had adapted his successful social comedy Pygmalion for the screen for a major international production. Directors Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard masterfully realised his ideas. Shaw's dialogue and his astute social criticism remained largely intact in the film, which was both an artistic and commercial success. Shaw's drama was later adapted as a musical under the title My Fair Lady. The idea, based on Ovid's Pygmalion myth, that a man moulds a woman according to his own ideas (in Shaw's drama, by teaching the simple flower girl to speak like a lady of high society) is apparently indeed timeless.

Shaw was considered a difficult and unruly man, known for his sharp mind, critical attitude and provocative personality. How did that make itself felt?

Katharina Rennhak: Shaw was undoubtedly witty and his idealism and commitment to a better society are admirable. However, he did not only make friends with his moral and political uncompromisingness and mercilessness and his sharp tongue. With regard to Shaw's personality, Fintan O'Toole, the Irish journalist and cultural critic, finds that George Bernard Shaw is more like David Bowie than William Galdstone, more like Bob Dylan than Anthony Trollope, in that he was one of the first "great masters of self-invention": "A nobody who captured the zeitgeist". Shaw saw through the mechanisms of the mass media very early on and recognised that roles are not only played on stage, but everywhere. He therefore not only imagines literary characters and worlds, but also meticulously creates his own persona "GBS" - not to pretend or deceive his audience, but to achieve his goals. He does not become a hypocrite because, according to Fintan O'Toole, he always acts like a magician who reveals his own tricks. This kind of self-dramatisation makes Shaw an early representative of celebrity culture. The acronym he created, GBS (one can hardly speak of a pseudonym), became a global brand that Shaw built up through his own efforts and skilful use of all the media available to him. His appearance, for example, is iconic. In the images of Shaw, which are reproduced en masse and distributed all over the world, his long reddish-brown and later white beard in particular becomes a recognisable feature. Interestingly, the Oxford English Dictionary also testifies that the term 'Shavian', in the sense of 'a fan of G.B. Shaw', was first used and disseminated by Shaw himself. (The use of 'Shavian' in the sense of 'typical of Shaw' and 'as in the work of Shaw' had already been brought into circulation by others). Incidentally, GBS was already a brand before Shaw slowly became a successful playwright from the late 1890s onwards. In the years before that, Shaw and GBS had made a name for themselves as cultural critics, journalists, writers of letters to the editor and political speakers for the Fabian Society. As early as 1891, the Sunday World stated: "Everybody in London knows Shaw. Fabian, Socialist, art and musical critic, vegetarian, ascetic, humourist, artist to the tips of his fingers, man of the people to the tips of his boots. The most original and inspiring of men - fiercely uncompromising, full of ideas, irrepressibly brilliant": Everyone in London knows Shaw. Fabian, socialist, art and music critic, vegetarian, ascetic, humourist, artist through and through, man of the people to the tips of his toes. An extremely original and inspiring man - relentlessly uncompromising, full of ideas, immensely brilliant. (Quoted from Christopher Wixson)

Photo: George Bernard Shaw (1936) public domain

Inspired by literature, he became a vegetarian very early on. How did that come about?

Katharina Rennhak: Shaw had been a great fan of the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley since his teenage years; and his decision in favour of vegetarianism is closely linked to his fascination with Shelley's political poetry and his radical criticism of social injustice. Shaw is said to have first slipped into the role of GBS at a meeting of the Shelley Society, when he announced that he was "like Shelley, a socialist, an atheist and a vegetarian". Shaw remained a vegetarian all his life, was an avowed non-smoker and did not drink alcohol. His lifestyle was a recurring theme in the media and Shaw never tired of explaining that thanks to his abstinence and vegetarianism he was able to economise and at the same time do something good for his health. In his typical manner, he skilfully used the pronounced public interest in his lifestyle to campaign for animal welfare and the creation of a state health service and to criticise the medical-industrial complex.

You also represent the EFACIS Centre for Irish Studies in Wuppertal at the University of Wuppertal. To what extent can George Bernard Shaw be described as an Irish author? His entire oeuvre is closely associated with London.

Katharina Rennhak: George Bernard Shaw's career began in London, from where he worked for most of his life. However, he was born in Dublin, where he also spent the first twenty years of his life. He grew up very close to the notorious tenement neighbourhoods where Dublin's working class eked out an existence. Life in these urban slums was characterised by unemployment, poverty and a general lack of education and opportunity. The Ireland of his youth thus vividly demonstrated to Shaw the structural obstacles that impede individual fulfilment, social progress and constructive opinion-forming processes - the very social problems that he later made a central concern of his work. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Shaw's first box office success, which established his reputation as a playwright, is a play that deals with British rule over Ireland and issues of nationalism: John Bull's Other Island (1904). In this drama, Shaw analyses the relationship between England and Ireland relentlessly. On the one hand, he shows how the English simultaneously romanticise romanticise and exploit Ireland. On the other hand, he makes clear how many Irish are in a state of dependence on Great Britain and economic and social stagnation. comfortably settled. Their criticism of oppression and their national rebellion remain pure rhetoric in Shaw's work. In short, John Bull's Other Island is a biting social satire that takes a critical swipe at all the players in the colonialist-capitalist system. However, it does so in such a witty and entertaining way that King Edward VII laughed so hard at the première that his chair broke - at least according to an often-told anecdote.

Shaw was very political, but also ambivalent in his statements. He sometimes sympathised with the Nazis, but also vehemently opposed them. How can you explain his attitude?

Katharina Rennhak: This is a very important but also difficult question that requires a differentiated approach. I don't want to fob readers off with the often formulaic answers that can be found in many shorter overviews of this aspect of Shaw's thinking. One common line of argument is that Shaw may sometimes have expressed himself in a misleading way or that his satires were sometimes simply not understood correctly by everyone. I find this argument futile and dangerous. Because yes, of course, anyone - even Shaw - can express themselves incorrectly or make mistakes as an author and simply write a bad satire that misses its target. Neither is morally reprehensible. But if a public figure accidentally makes a morally contradictory statement or writes a bad satire, I would expect that person to take a clear stance as quickly as possible in the subsequent public debate about these morally dubious, contradictory statements. However, Shaw was probably unable to do this at times because not only his rhetoric but also his attitude was contradictory in some respects. A concrete example of this are his controversial and hotly debated statements on the then much-discussed topic of eugenics, i.e. the question of whether and in which cases the state should be allowed to kill human life. Shaw repeatedly spoke out in favour of eugenic practices in very different texts and contexts. Ultimately, it is difficult to decide what is meant seriously and what is not, as no clear overall picture emerges. In any case, there is and remains no doubt that Shaw was at times an admirer of Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini. Short accounts like to "answer" this problem with the sentence that he may have admired these politicians, but not their political programmes as a whole. In my opinion, however, such a succinct statement does not help anyone. Fintan O'Toole's judgement is more nuanced. He states unequivocally that Shaw, like many of his contemporaries, was frustrated by the protracted democratic disputes in Parliament and wanted a strong man who promised the rapid implementation of his political ideas. According to O'Toole, Shaw's failure ultimately lay above all in the fact that, as the great, wise thinker and seer GBS, he failed to recognise that the political ideas of Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini were by no means congruent with his own. "The great sceptic," says O'Toole, "allowed himself to be seduced into believing exactly what he wanted to believe: that the totalitarian regimes of Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin were harbingers of genuine human progress and true democracy."

Shaw died aged 94. What would you consider to be his most important contributions to culture and society?

Katharina Rennhak: The playwright Sean O'Casey once said of his colleague: "Although Shaw never wrote a socialist play, he was the greatest socialist of the Western world in his century." He is perhaps referring to Shaw's greatest achievement. As a convinced socialist who never hid his political opinions, he always made a point of giving space to different convictions in his plays. Characters who hold positions that are recognisably Shaw's own are not portrayed in a one-dimensionally positive way. These characters also make mistakes and present their philosophical theories and political viewpoints, but not without sometimes becoming entangled in contradictions. At the same time, characters with convictions that do not coincide with those of the author are not negatively exaggerated. As a rule, they are just as rhetorically convincing as their dialogue partners. You could also say that Shaw's faith in the good in people and his hope that society can be changed for the better are deeply rooted in the idea that constructive dialogue with sometimes conflicting opinions ultimately always enriches social interaction. All of this is absolutely relevant today. In short, and with recourse to more current buzzwords, one could say that what we see demonstrated in Shaw's plays in a practical and entertaining way is the equally paradoxical and positive interaction of tolerance of ambiguity, determined political commitment and the ability to engage in dialogue.

Uwe Blass

Katharina Rennhak studied English and German at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich and at St Patrick's College Maynooth, Ireland. From 1997 to 2009, she taught English literature at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. Since 2009, she has been a professor of English literature at the University of Wuppertal. Katharina Rennhak was from 2019-2025 President of the European Federation of Associations and Centres of Irish Studies (EFACIS). She has been a member of the IASIL Executive (European Representative) since 2016 and a long-standing member of the Centre for Narrative Research at the BUW.