Censorship and prohibitions in works of art of the modern era

Dr Doris Lehmann / Art History

Photo: Private

The creative handling of censorship and prohibitions in modern works of art

Art lecturer Doris Lehmann on polemic artists’ disputes

Ms Lehmann, you have just published a new book entitled “Bildpolemischer Künstlerstreit” (Polemic Artists' Disputes), dealing with 18 cases of artists' disputes in the period from 1525 to 1763, which are reflected in your works. How did people argue pictorially or graphically back then?

Doris Lehmann: There was no one-size-fits-all recipe for designing a controversial image, i.e., a work of art that made a vivid contribution to the resolution of a dispute. Back then, disputes were not emotionless; artists are only human. The results were therefore as varied as the people involved, the respective circumstances, and the trigger. There are two clearly distinguishable ways of conducting a dispute: on the one hand a pictorial polemic detail was integrated into a work of art – these examples can even be found in commissioned works – and on the other hand an entire object was created in response to the dispute. The spectrum ranges from a complex allegorical painting to a drawing enclosed with a letter as well as a printed artist's pamphlet. There were also anti-criticisms, i.e., works of art that were produced in response to a previous controversial painting.

These were creative ways of dealing with defamation, censorship, and moral prohibitions on offensive depictions of people. How do you recognise something like this today?

Doris Lehmann: There are various ways of recognising such examples. There are historically documented cases in which surviving letters, pamphlets or court records point us to controversial depictions. The controversial artists themselves ensured the legibility of some motifs by referring to swearwords and proverbs. Comparisons and image analyses also reveal the particularly exciting area of self-censorship: sensitive motifs were erased or moved to a tolerable position. It was and still is more difficult to recognise ambiguous or ambivalent signs with which attempts were made to circumvent censorship. We can discover these because, like woven fabric defects, they attract attention, stimulate reflection and draw attention away from the main subject and onto the dispute.

What are some leitmotifs of visual language artists used, for example, to express their criticism?

Doris Lehmann: Ignoring clients or critics was one important topic. Midas’s ears were used as a motif: they resemble donkey ears and are often confused with them. In terms of content, however, the difference shifts the message, as Midas was a legendarily bad judge. The reference to him was therefore an excellent way of denying opponents the ability to criticise. The staging of eye defects also served as a symbol of a lack of judgement. An unused oar, on the other hand, denounced a lack of leadership skills. The accusation of laziness was disguised as sleep. Satyrs represented mockery and slander. As it was usually also about payment behaviour, we often find (money) sacks in the picture.

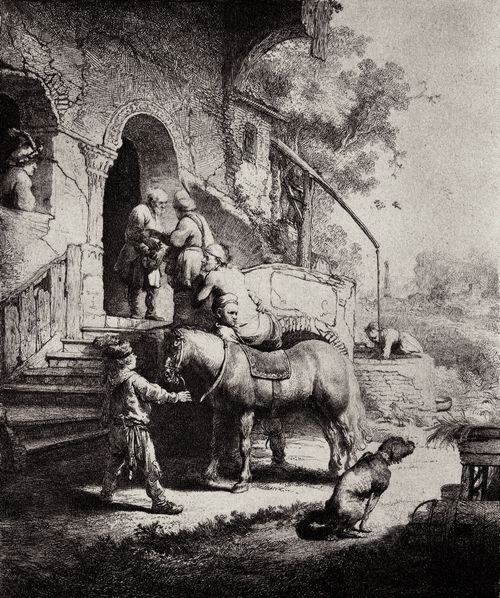

Pictorial representations of dogs are also frequently used as a motif for criticism. What significance did they have in pictures?

Doris Lehmann: Dogs are an ambiguous motif. When they were used in polemic images, their depictions are part of a moral-philosophical tradition that goes back to the disrespectful and shameless criticism of Cynics such as Diogenes and Zoilos. As outsiders to society, Cynics did not abide by its rules and pointed out social evils. The proverb “The dog is bold in his dung”, which can be traced back to the humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam, justified Rembrandt's depiction of a dog doing his business, for example. The associated statement was: my critic is not an authority on art, even if he thinks he is. Such a comment may not have been noble, but it was clear.

The Good Samaritan by Rembrandt (1633),

Photo: public domain

What impact could such a polemical artistic dispute have? Is it still possible to find out today?

Doris Lehmann: Yes, there is evidence, such as letters or court records, of the effects of polemical artistic disputes. A complaint could lead to the confiscation of the work, censorship and a penalty of honour. Federico Zuccari had to account for his actions in a libel trial after insulting people close to Pope Gregory XIII with a painting and its explanation. In 1581, the papal tribunal banished the painter from the Papal States. Other painters, such as Rembrandt, were not prosecuted, but alienated clients and lost support.

Every artist had to be particularly creative when it came to avoiding prosecution for their critical and offensive statements. Can you give us an example?

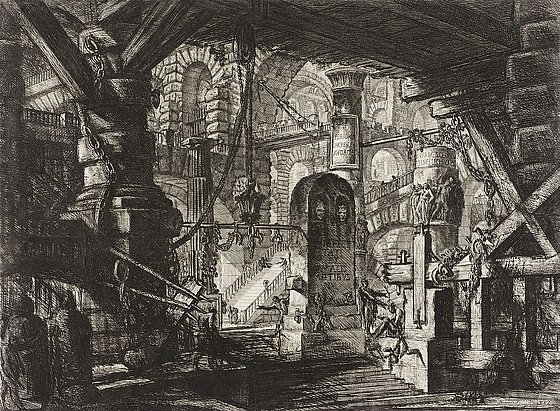

Doris Lehmann: Giovanni Battista Piranesi is an outstanding example of a graphic artist who repeatedly circumvented censorship. It is known that he sold, sent, and archived banned prints. For his pamphlet, he had the text printed in Florence and secretly brought to Rome. He even distributed a second edition of it, but “toned down” controversial image details by reworking printing plates and erasing inscriptions that could put him in danger. Contemporary witnesses were nevertheless able to identify the abbreviated names without great difficulty.

Print from the series 'The Invented Prisons' (1761) by Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Photo: public domain

In your book you write that the artists understood how to use their artworks as a medium of conflict and even as a weapon against their opponents. How should I visualise this?

Doris Lehmann: We have to realise how strongly personally addressed images can affect feelings and honour. For that reason, the creation of insulting and disgraceful paintings was banned. When artists visualised and exhibited or disseminated violent fantasies in response to criticism of their work, the aim was to emotionally offend their opponents and devalue them in society. The pictorial tradition dates back to the Middle Ages. Artists fuelled the fear of this socially devaluation by anchoring corresponding narratives in the culture of remembrance. Such anecdotes are still widespread today. If we look at Piranesi's pamphlet, we find a whole collection of highly symbolic punishments of honour, including the prominent staging of the shattered family coat of arms of his former patron. In terms of imagery, this was also aimed below the belt. Peaceful conflict resolution does not look like this.

What are the other research opportunities your new approach to pictorial works does offer academics?

Doris Lehmann: Methodologically and thematically, it opens up fields of research and new perspectives for studies in the social history of art and interdisciplinary controversy research. For example, there is still no networked research focusing on artists' pamphlets. I myself am already continuing my research into the artists' controversy after 1763, and there is still a lot to rediscover and reappraise.

Book tip:

Doris Lehmann

Bildpolemischer Künstlerstreit: Von Leonbruno bis Hogarth

Ad picturam, 2024

Uwe Blass

Dr Doris H. Lehmann is a trained photographer and studied Art History, Classical Archaeology, Provincial Roman Archaeology and Latin Philology at the University of Cologne, where she obtained her doctorate in 2005. In 2018, she habilitated at the University of Bonn with a thesis on the dispute strategies of visual artists in modern times and has been a private lecturer ever since. She has been teaching art history at the University of Wuppertal as a research assistant since October 2018.