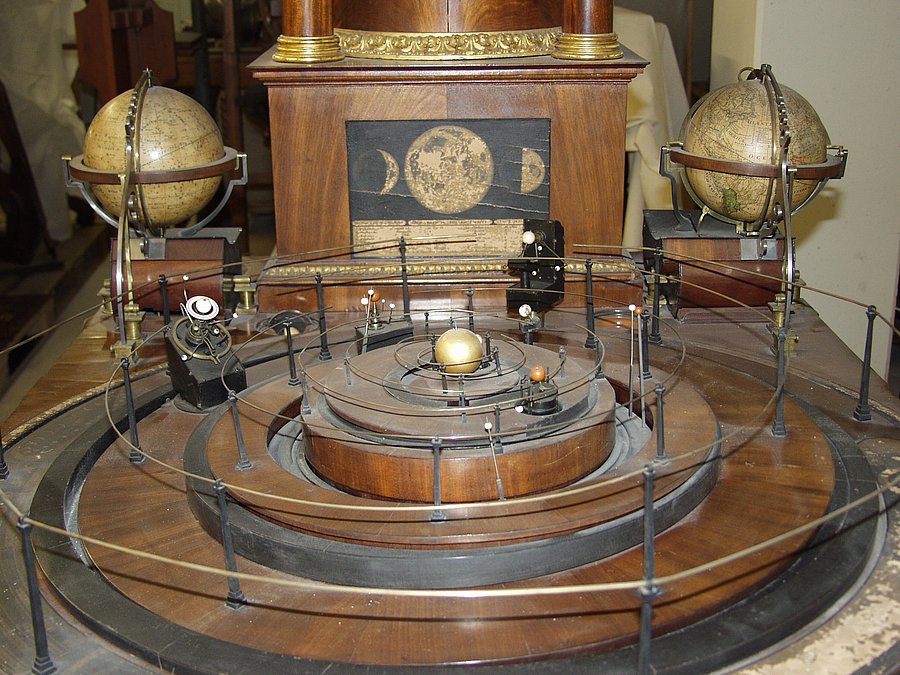

Table planetarium close-up from the front

Photo: Deutsches Museum

The historic Elberfeld desktop planetarium

In 1828, the Elberfeld carpenter Heinrich Aeuer completed an extraordinary instrument, which today awaits its return to Wuppertal in the catacombs of the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

The 19th century saw a steady increase in the popularisation of science among the population. Scientific enthusiasm was not limited to academic circles. An extraordinary example of this is the Elberfeld carpenter Heinrich Aeuer, who built a fascinating desktop planetarium between 1820 and 1828 and wove in conjectures about the planets that only proved to be scientifically correct 150 years later.

Michael Winkhaus/ Carl-Fuhlrott-Gymnasium / Physics Bergische Uni

Photo: Private

Michael Winkhaus, Director of Studies at Carl-Fuhlrott-Gymnasium and lecturer in astronomy as part of the physics teacher training programme at the university of Wuppertal, has been studying this wonderful object for many years and now wants to bring it back to Wuppertal together with physicist Johannes Grebe-Ellis and historian Sabrina Engert. And the chances are good.

A carpenter's work with astronomical content

All that is known about Heinrich Aeuer today is that he ran a carpentry business between Elberfeld and Barmen, Winkhaus says. As a teenager, he had contact with astronomy through his confirmation classes and even wanted to study it, but his father forced him to take over his father's carpentry business. ”That's how these dual interests came about,” the graduate physicist explains, ”i.e., carpentry work, but with astronomical content. That is the essence of this desktop planetarium.”

Sabrina Engert/ History of Science and Technology

Photo: Uniservice Third Mission

The planetarium is the size of about four school desks placed side by side and shows everything that can be experienced in astronomy in the sky. ”So, you can follow the movement of the planets, the phases of the moon, the measurement of time, both the daily rotation of the earth, which makes up our time of day, with solar time and sidereal time. You can also see the months. It all works via a crank mechanism. This means, if you turn a crank, everything starts to move, just like in reality,” Winkhaus says, describing the fascinating object. You can also switch on several gears to speed up processes for demonstration purposes. Before the much later introduction of projection planetariums, you could already see everything on this tabletop planetarium.

The Elberfeld table planetarium

Photo: Deutsches Museum

Founding of the school in 1830 and purchase of the desktop planetarium

The Höhere Bürger- und Realschule Elberfeld, forerunner of today's Carl-Fuhlrott-Gymnasium, was founded in 1830 and established in Herzogstraße. The school's founding phase also included the purchase of the desktop planetarium for a considerable sum, even at that time. ”Back then, the sum was indicated in thalers. It was a worker's two-year salary, which today would be estimated at around eighty to one hundred and fifty thousand euros. I don't think Aeuer built the planetarium purely for commercial reasons, because he also wrote two books, which are available in the city archives. You can see his enthusiasm for astronomy and his obsession with detail.” In the school's own archive Winkhaus was even able to find contracts for the maintenance work carried out by Aeuer himself in the early years. The school moved to Robert-Daum-Platz in 1900, where the Sankt Laurentius Schule is located today. There, the tabletop planetarium was placed in a glass case and stood in front of the assembly hall. Winkhaus assumes that it was no longer fully functional then. In this context it is remarkable that pupils at both school locations had a great interest in astronomy , so that an additional observatory was built at the time. However, the observatory at Laurentius School, which was destroyed in the war, was never rebuilt.

Tabletop planetarium in the former exhibition in Munich

Photo: German Museum

1903 - Foundation of the Deutsches Museum in Munich

”In 1903, the Deutsches Museum in Munich was founded by the German Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II. The founding father was Oskar von Miller, who had the idea of establishing a hands-on museum as the first museum in the world. The exhibits should be hands-on,” Winkhaus says. This completely modern, new museum concept is now one of the largest hands-on museums in the world. ” The Wuppertal chemist Carl Duisberg and the Wuppertal-based company Bayer were among the early supporters of the Deutsches Museum. Although the magnificent modern building was now finished, it had to be filled with life because there was simply a lack of exhibits. ”So, the museum operators started looking for interesting objects. Duisberg from Wuppertal remembered the beautiful desktop planetarium. And he talked the then director Börner into parting with it, so to speak, as he didn't really want to give it away because he was interested in astronomy himself,” Winkhaus explains. He therefore loaned the desktop planetarium to the museum and drew up a contract to this effect. ”It was then on display in the planetarium exhibition until 1990,” he continues. ”However, the museum concept was then completely changed and the planetarium exhibition no longer existed, so all the exhibits, including the desktop planetarium, were moved to the basement.” As part of a work placement, Winkhaus then commissioned two pupils from his grammar school to produce documentation on the desktop planetarium, which is now available. It also contains the decoding of all the astronomical functions. And this documentation lead to the idea of bringing the object back to Wuppertal.

Cooperation between the University of Wuppertal and Carl-Fuhlrott-Gymnasium

The three protagonists mentioned are hoping for further support from students and pupils and are planning a potential return of the planetarium in 2030. ”The school was founded in 1830,” Winkhaus explains, ”which means that in 2030 we will be celebrating the 200th year of our existence. Therefore, it would be wonderful if we could present an exhibit for this anniversary date, even in a restored form, that dates back to the first days of the school's history.” Five years of planning is also a good amount of time to be able to realise everything. Of course, he is particularly grateful for the support of his fellow campaigners. ”A school is working together with the Department of History of Science and Technology and the Department of Physics at the university. This cooperation also emphasises our seriousness about bringing the planetarium back to Wuppertal and raising the necessary funding, as the instrument also needs to be restored.”

Rich detail and prophetic interpretation

The Elberfeld desktop planetarium has a wealth of details to offer, which are also spectacular. “Heinrich Aeuer was an incredible guy”, Winkhaus states. “I'm an astronomer myself and I'm completely amazed at the detail with which he designed this desktop planetarium. These are not just the most important celestial functions. So, when you look at it you immediately see a Copernican planetarium, where the planets move around the sun. If you now take a closer look at the planets, you can see that there are a few more than there are today. The planets Ceres and Vesta, for example, are so-called minor planets that were still part of the planetary system back then because they are objects that move around the sun.” It should be noted that reasonably good telescopes had only existed since 1780, but Aeuer had already started building his planetarium in 1820.

”If you then look at the side of the desktop planetarium, you can see a celestial globe and an earth globe, both of which rotate, so that you can basically understand the different time systems that are used by rotating these globes. Then there is a small sphere at one point. You can see only half of it. It is also only painted black and white. This is the current phase of the moon for that day, which you can turn.”

Aeuer then added a very special, spectacular detail, which really left Winkhaus speechless. ”The planet Uranus was discovered by Wilhelm Herschel in 1781, just 40 years before Aeuer started building the planetarium. He gave the planet a ring, similar to that of the planet Saturn. But this ring is perpendicular to the orbit, we say to the ecliptic, while Saturn appears parallel or slightly offset in the sky. This is a rather unusual position for such a ring. It is remarkable that this ring was only discovered by the Voyage probe at the end of the 1970s. Firstly, it is interesting that Uranus has rings at all and secondly, that they have such an unusual position in relation to the ecliptic. So how does this carpenter know that?“

Winkhaus finds the answer in one of Aeuer's books. ”He says that Wilhelm Herschel saw little stars twinkling next to Uranus, stars that disappear and reappear. And Heinrich Aeuer now concludes from this that Uranus may also have rings that cover the stars from time to time. And from the blinking of these stars, he now concludes that they have an unusual position in relation to the ecliptic. That was his assumption and that's why he added it, but also noted that if he was wrong, the rings could be removed again. Today we know that the carpenter from Wuppertal was right.”

Kick-off event for the tabletop planetarium in the city library

The first launch event to reintroduce the Elberfeld desktop planetarium to the people of Wuppertal is scheduled for 7 October in the city library. At 6.30 pm, Winkhaus will decode the astronomical, spectacular, and unique aspects of this planetarium. Visitors will learn what used to happen in their city. Sabrina Engert concludes by emphasising once again: ”People can expect a really great presentation that will captivate them. I have already had the pleasure of hearing Michael Winkhaus speak in my seminar and my students were absolutely thrilled. He puts his heart and soul into it and is able to explain the topic in a way that even laypeople can understand. Astronomy enthusiasts as well as historians and city lovers will get their money's worth.”

Uwe Blass

Michael Winkhaus is a physics teacher, head of the student astronomy laboratory at Carl-Fuhlrott-Gymnasium, and a contract lecturer in astronomy as part of the physics teacher training programme at the University of Wuppertal.

Sabrina Engert is a research assistant and doctoral candidate in the Department of History of Science and Technology at the School of Humanities at the University of Wuppertal and the Interdisciplinary Centre for Science and Technology Studies (IZWT).

Johannes Grebe-Ellis is a professor of physics and didactics of physics at the School of Mathematics and Natural Sciences at the University of Wuppertal