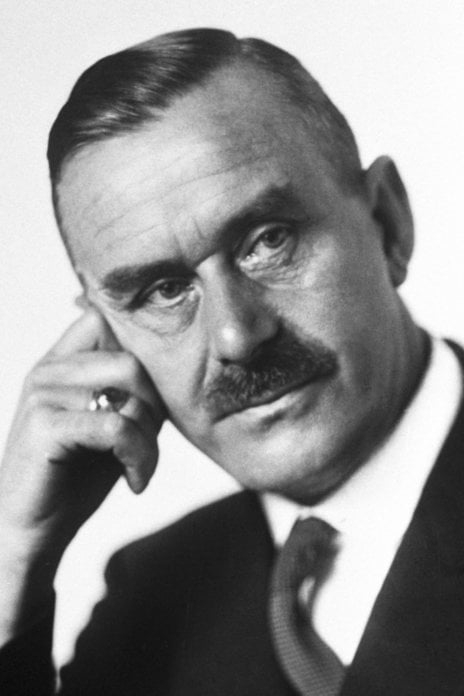

150th birthday of Thomas Mann

PD Dr Arne Karsten / History

Photo: Sebastian Jarych

The man who wanted to bring ‘a little higher cheerfulness’ into the world

Arne Karsten on the 150th birthday of the writer Thomas Mann in connection with a lecture event at the University of Wuppertal

When asked what the first thing were that would come to mind when he hears the name Thomas Mann, historian Dr Arne Karsten from the University of Wuppertal spontaneously replies: “Buddenbrooks and a sense of duty!” The novel, published in 1901, is the beginning of the unique success story of an author who, as Karsten explains, “had a tremendous, tenacious determination to fulfil his task against all internal and external resistance in order to 'bring a little higher cheerfulness into the world' with his life's work, as Thomas Mann himself put it”.

The work characterised by personal life experiences still fascinates today

Thomas Mann was born 150 years ago on 6 June 1875 in Lübeck, the city in which one of his most famous novels, ‘Buddenbrooks’, a biographical work, was later set. “Throughout his life, Thomas Mann always emphasised that he hadn't actually invented anything,” Karsten says. “His work is extremely strongly influenced by personal life experiences, even where it is set in very different contexts.” This influence can also be seen, for example, in the novels 'Joseph and His Brothers' or 'The Chosen One'. In 'Doctor Faustus', his great novel, which he wrote in the wake of the fall of Nazi Germany, the biographical element once again comes to the fore with almost overwhelming intensity. “He said it was a late ‘little brother’ of Buddenbrooks. He was almost obsessed with autobiographical furore, with describing family histories, including family tragedies. What he had already planned in his younger years, a sequel to 'Buddenbrooks', albeit set in a different setting, he realised in 'Doktor Faustus'.”

His novels were translated many times, the Buddenbrooks alone into around 40 languages. His public impact makes him one of the most important storytellers of the 20th century to this day. “No writer of his generation is still read as much today as Thomas Mann. And he is one of the most important employers for Germanists among the writers of the 20th century.”

Success only possible thanks to the woman at his side

Without his wife, Katia Mann, Thomas Mann's life's work would never have been realised. He always knew that. In his speech on her 70th birthday, he said: “As long as people remember me, she will be remembered.” She was the good spirit, Karsten knows, who always had his back. “Practical in life and coming from a very wealthy background - the Pringsheim parents belonged to Munich's upper class - she was not only a very caring, attentive mother to the six children they had together, but also her husband’s manager in a way. She was the woman who gave him the time to concentrate on his work,” the historian explains.

Thomas Mann worked on the novel 'The Magic Mountain' for nine years

”The First World War simply intervened,” Karsten says, explaining the long period of time in which his novel 'The Magic Mountain' was written, “the irritation, the fundamental questioning of his entire intellectual and artistic existence. The battle, which was also an ideological battle, simply did not allow him to concentrate on the higher, ironic and distanced play with artistic themes, as he repeatedly realised himself. However, it forced him to give an account of his own position in the battle of opinions.”

Thomas Mann, 1929, public domain

Thomas Mann leaves a poisoned Germany in 1933

Thomas Mann was also a political man by necessity. He defended the Weimar Republic and emigrated to the USA after the Nazis came to power. He told the New York Times in 1938: “It [exile] is hard to bear. However, what makes it easier is the realisation of the poisoned atmosphere that prevails in Germany. It makes it easier because in reality you lose nothing. Where I am is Germany. I carry my German culture within me. I live in contact with the world and I don't see myself as a fallen human being.” Even when he was in exile, he always got involved. His 55 radio addresses published by the BBC between 1940 and 1945 under the title “Deutsche Hörer” (German Listeners) are well known. ”Thomas Mann recognised the fatal development in Germany very early on and, as he himself said, tried to do what he could to stop it, using his weak powers”, Karsten comments. “When this was no longer possible, exile began, which is somewhat more complicated. He was living in Munich and had given a major lecture there in February 1933 on the 'Sufferings and Greatness of Richard Wagner'. He then went on a lecture tour to Holland, followed by a short holiday in Arosa, Switzerland. There he was surprised by a 'protest from Munich, the city of Wagner', where Munich intellectuals and those who counted themselves among them dismissed the lecture as un-German and intolerable in an outrageous and grotesque manner. And then he realised that there was no point in going back to Germany.” Thomas Mann initially stayed in Switzerland, then finally went to America in 1938 and only returned to Europe after the Second World War.

No return to Germany

However, Thomas Mann did not return to Germany. He spent the rest of his life in Switzerland for two reasons, Karsten says: “He was afraid of the destroyed cities, he wrote himself, but also of the destroyed souls. After all, with the fall of the Third Reich, the Nazis had not suddenly. There were many people who resented his exile and the fact that he didn't have to live through what was happening in Germany.” However, exile was not voluntarily chosen by him. “He had the feeling that he wouldn't feel comfortable in Germany and this is where the idea of commitment to the work comes into play again. The atmosphere in Germany was so difficult, so characterised by misunderstandings and people who wished others ill, that he feared for his concentration and inner peace.” He had been fond of Switzerland since his honeymoon with Katia in Zurich and Lucerne in 1905 and after his return from America he said: “Switzerland is the country where you can say the completely un-German thing in German, and that is why I love it!”

A difficult person

“What a strange family we are,” Klaus Mann, one of his sons, later wrote. Thomas Mann himself said of himself: 'Someone like me should of course not bring children into the world. “He was certainly very difficult,” Karsten says about the man of letters and smiles, “but the nice genius next door who also helps with the gardening in an uncomplicated way is generally rather rare.” A man of Thomas Mann's sensitivity and fragility suffered from depression and a variety of illnesses throughout his life. “If you look at his diaries he kept very carefully and read how often he went to the dentist, you almost have to wonder when he ever got round to writing. For all that he once attributed to Richard Wagner, he was sick in a 'healthy way'. The basic vitality of his life, the aforementioned firm determination to complete his work, which he regarded as imposed, ensured that his will always triumphed over his countless illnesses.”

At Thomas Mann's funeral in 1955, Carl Zuckmayer aptly described his significance for German literature as follows: “At this coffin, a voice falls silent. A life has been fulfilled that was dedicated to only one thing: the work of the German language, the continuation of the European spirit.”

Conference at the University of Wuppertal to mark the 150th anniversary of Thomas Mann

In order to mark the 150th birthday of the exceptional writer, PD Dr Arne Karsten organised a conference along with the German scholar Prof. Dr Michael Scheffel. Based on the quote from the novel 'Confessions of Felix Krull': "Being is not well-being; it is pleasure and burden", they will be presenting five lectures on Thomas Mann's work and political attitude on 4 June from 2:00 pm in the senate room of the University of Wuppertal, building K, level 11, room 07. Admission is free and interested visitors are very welcome.

For further information on the programme, please contact Prof Karsten: akarsten[at]uni-wuppertal.de

Uwe Blass

PD Dr Arne Karsten (*1969) studied art history, history and philosophy in Göttingen, Rome and Berlin. From 2001 to 2009, he was a research assistant at the Institute for Art and Visual History at the Humboldt University of Berlin and head of the research project “REQUIEM” - The Roman Papal and Cardinal Tombs of the Early Modern Period, www.requiem-projekt.de. He has been teaching as a junior professor since winter semester 2009 and as a private lecturer in modern history at the University of Wuppertal since his habilitation in 2016.