A victim of Nazi rule: the economist Cläre Tisch

Prof Dr Hans Fambach /Economics

Photo: Mathias Kehren

“Isn't it terrible to see the ice desert in front of you at the age of 26?” (Cläre Tisch)

The economist Hans Frambach on the impressive economist from Elberfeld, Cläre Tisch, who was murdered by the Nazis

“It gives me hope for the future, into which I am now going, to know that I can count on your help when help is possible again,” the Elberfeld economist Cläre Tisch wrote to her highly esteemed doctoral supervisor Joseph A. Schumpeter, seven days before she was murdered by the Nazis. Wuppertal economist Hans Frambach analysed the impressive life of the academic, who was killed in 1941 and whose work continues to have an impact today.

Cläre Tisch

“Dr Cläre Tisch was a remarkable woman who stood up for her convictions,” Frambach explains at the beginning, describing the career of a young scientist that came to an abrupt end at the hands of the National Socialist regime. ”She was born in Elberfeld on 14 January 1907, spent her childhood and school years there and passed her Abitur exams in 1926. In the summer of 1929, she completed her degree in Economics at the University of Bonn, after which she attended further courses, in particular with Joseph A. Schumpeter (Schumpeter is the namesake of the School of Economics at the University of Wuppertal, editor's note), who also advised her to pursue a doctorate on the subject of 'Economic Accounting and Distribution in a Centrally Organised Socialist Community'." Tisch completed her doctorate in record time at the end of July 1931. She continued to work at the University of Bonn until 1933, but then had to leave under pressure from the Nazis because she was Jewish. “Until 1936," Frambach reports, “she pursued various activities before obtaining a position at the Zentrale für Jüdische Pflegestellen und Adoptionsvermittlung, Kinder- und Jugendschutz des Jüdischen Frauenverbands e.V. (Centre for Jewish Foster Care and Adoption Placement, Child and Youth Protection of the Jewish Women's Association e.V.), Wuppertal-Elberfeld, which she carried out with great commitment and passion until her deportation from Wuppertal. On 10 November 1941, Cläre Tisch was deported from Elberfeld to Minsk together with her two sisters, brother-in-law, and niece. The journey took three days. In all probability, she was murdered on 15 November 1941.”

Addition to the school’s name leads to a study of Cläre Tisch

Because the School of Business and Economics focussed on the topics of innovation, dynamic entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship and structural and cyclical economic development, the researcher explains, in October 2008, the University of Wuppertal added the name ‘Schumpeter School of Business and Economics’ to the name of the school. “This decision was preceded by an intensive and interdisciplinary study of the person of Joseph A. Schumpeter, which also included the search for connections between Schumpeter and Wuppertal.” Although it was not possible to clearly define Schumpeter’s proximity to Wuppertal, the research repeatedly came across two economic personalities: Cläre Tisch and Hans Singer (a development economist born in Wuppertal. The Hans-Singer-Weg in Wuppertal Elberfeld was named after him in 2024 (editor’s note). “From here, the path to further dialogue with both was not far away,” Frambach continues. “I became very intensively involved with Cläre Tisch in 2011, when the Wuppertal entrepreneur Ralf Putsch asked me to open up the correspondence between Tisch and Schumpeter from the Harvard University Archives for a joint project with Dr Ulrike Schrader, the director of the Alte Synagoge Wuppertal meeting place.”

Cläre Tisch memorial plaque at the old synagogue

Photo: CC0

The verbatim transcripts of an exceptional scientist

Joseph A. Schumpeter took over the chair of economic political science at the University of Bonn in 1925. “He held it until 1932, before moving to Harvard University.” After a few detours, Tisch enrolled to study economics in Bonn in 1928 and passed the ‘diploma examination for economists’ on 10 July 1929,” Frambach says. Only two years later, she completed her doctorate under Schumpeter. “Cläre Tisch admired Schumpeter, took verbatim notes of his lectures and seminars and, together with fellow students such as August Lösch, Hans W. Singer, Wolfgang F. Stolper, and Herbert Zassenhaus, certainly belonged to the ‘inner circle’ of Schumpeter's students. Her correspondence shows that her notes were really marvellous and she sold them to her fellow students for good money,” the expert smiles. She understood very well how to assert herself at the time. You don't get the impression that Cläre Tisch had any problems in this male society. ”The real problems arose with National Socialism, immediately after the national socialists came to power in 1933, and in a way that a person could not defend themselves against.”

Tisch’s doctoral thesis - the best work on the subject to date

Cläre Tisch received her doctorate in 1931 with the topic ‘Economic accounting and distribution in a centrally organised socialist community’. In economic circles, her work is considered very remarkable. Frambach explains why this was the case: “In the 1910s and 1920s, there was a lively debate about the efficiency of the economy in a socialist versus capitalist system, which was initiated in economic theory by an essay by the Italian economist Enrico Barone in 1908. Barone had mathematically demonstrated the identity of a general equilibrium in a centralised system and one under purely competitive conditions.” He believed he could achieve the same results in a socialist system on the basis of mathematical calculations. ”But against the backdrop of significant historical events such as the Russian October Revolution in 1917 and the enormous problems that had arisen in the course of the First World War, the polarisation between the positions increased and reached a climax in the complete rejection of a socialist system,” Frambach explains. “It is precisely in this so-called socialist calculation debate that Cläre Tisch’s doctoral dissertation can be located, as she investigated whether the socialist economy can be regarded as an economy at all in the sense of rationally weighing up costs and returns.” In her work, she impressively demonstrates that, regardless of the question of centralised planning or free competition, the determination of equilibrium prices is at least theoretically possible if the allocation mechanism (allocation of limited resources, editor’s note) strictly follows the principle of scarcity. “It is important to emphasise that a ‘socialist solution’ is only formally presented and that in large parts of her work Cläre Tisch criticises socialist approaches in depth.” Schumpeter himself was in any case convinced by Tisch's work and wrote in his review of the work of ‘certainly the best that has been achieved so far within this problem area’. Cläre Tisch is often interpreted as a socialist, but the economist disagrees and says: “Although Cläre Tisch, like Schumpeter, recognised the great humanitarian objectives of socialism of equality and freedom from need and the resulting starting points for a critique of capitalism, I am firmly convinced, also in the consideration of her scientific oeuvre, that she must rather be interpreted as a market economist in the tradition of the Austrian school, as represented by Schumpeter.”

1933 - 1941 Tisch keeps her head above water with other jobs

Regardless of her great academic talent - she researched antitrust issues and wrote two books that were published in the very prominent series Industriewirtschaftliche Untersuchungen (Industrial economic studies) in 1933 and 1934 - Tisch had to leave the university in 1933. ”Since the Nazis came to power, Cläre Tisch was subjected to various forms of repression, which of course were not limited to her professional activities. Her events were boycotted, hardly anyone dared to listen to a Jewish woman anymore. Even a temporary job as a repetiteur could not be maintained.”

Tisch moved back in with her family in Wuppertal, travelled a little and earned her living through various jobs. According to Frambach: ”She worked as a typist in Cologne and as an office clerk in a shoe shop in Solingen. She had a longer-term job from 1936 to 1941. She held the position of 'secretary' at the Zentrale für Jüdische Pflegestellen und Adoptionsvermittlung, Kinder- und Jugendschutz des Jüdischen Frauenverbands e.V. (Central Office for Jewish Foster Care and Adoption Placement) in Wuppertal-Elberfeld, an institution of the Jewish Women’s Association, and was primarily responsible for organising and arranging foster care and adoption placements for Jewish children, especially in times of increasing persecution. The founder of the adoption centre and pioneer of Jewish social work was Clara Samuel (Samuel was the founder of the Elberfeld branch of the Jewish Women’s Association, editor’s note), and Cläre Tisch worked closely with her.”

Letters between Schumpeter and Tisch illustrate the hopeless situation

“Letters between Cläre Tisch and Joseph Schumpeter from the years 1933 to 1941 have been preserved,” Frambach says. Moreover, the correspondence from 1933 already clearly shows the oppressive situation for Jewish life in Germany caused by the Nazis. “In 1938, Cläre Tisch had applied to the American consulate in Stuttgart for permission to emigrate to the United States, but she herself considered it unrealistic to realise this step because of the waiting times of up to five years.” In 1938/39, Schumpeter himself had issued Cläre Tisch a letter of guarantee (affidavit) for her departure to the USA, which he repeated in 1941. However, the actual conditions for emigration were already so restricted that it was in fact impossible to fulfil them. ”In October 1941, the deportation of 53,000 Jews from the Reich to the ghettos of Lodz, Minsk, Kovno, and Riga in the occupied Eastern European states began. On 8 November 1941, two days before the Tisch family was deported, Cläre Tisch wrote to Schumpeter about the futility of trying to emigrate and a hopeful plea. It reads: ’[...] I did not write for so long because the changed immigration situation made any steps and efforts pointless, and because I did not want to trouble and bother you unnecessarily. I know how short your time is! Today, too, I would only like to ask you - the situation is unchanged - for the following: keep up your goodwill and willingness to help me, should any help be possible in later times - and don't do anything for me until I write to you and ask you to do so. I will be leaving Wuppertal the day after tomorrow and do not yet know what my new address will be, nor do I know whether I will have the opportunity to inform you of it as soon as possible. It gives me hope for the future, which I am now entering, to know that I can count on your help when help is possible again.’”

People today can hardly comprehend what was going on in the minds of the victims back then. “There are investigations into what must have been going on psychologically in people's minds and that is more than depressing,” Frambach says. ”I've done a lot of research for an essay that will be published soon. And when you read the reports about these transports, the mechanics with which people were processed, how cattle were organised and loaded, it can only make you sick. They went about it with absolute contempt for humanity.”

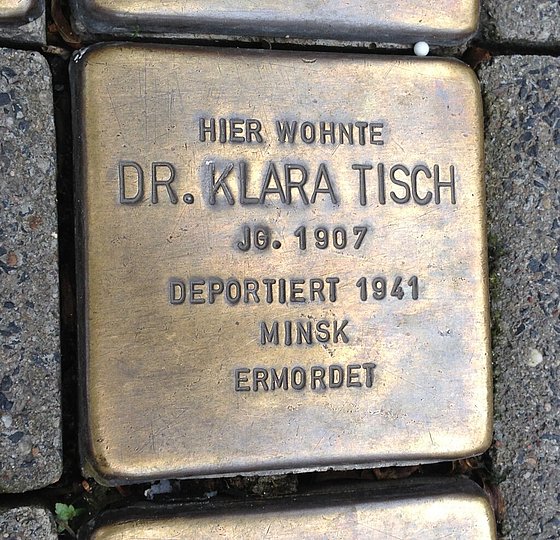

Cläre Tisch stumbling block

Photo: CC BY-SA 3.0

Cläre Tisch included in the list of women’s places in North Rhine-Westphalia

Stolpersteine are small memorial plaques made of brass that commemorate the victims of National Socialist terror. The stolpersteine of Cläre Tisch and her family - her older sister Marie, her younger, deaf sister Gerda, Marie’s husband Leo Marcus, and their daughter Arnhild Adele - were laid in 2008 at Neumarktstraße 8 (formerly Hermann-Göring-Straße 46, before that Walther-Rathenau-Straße 46) in Wuppertal Elberfeld, Frambach says. “It was the place where Cläre Tisch had lived with her relatives since leaving her flat in Bonn. Following the ‘Law on the Tenancy Relationships of Jews’ of 30 April 1939, the Tisch family was forced to give up their flat and move into one of the so-called Jewish houses at Distelbeck 21 in Wuppertal-Elberfeld, where they lived until their deportation to Minsk on 10 November 1941.”

In 2024, a memorial plaque was erected for Cläre Tisch at the Old Synagogue in Wuppertal as part of the Women's Places project. “At the ceremony on 9 June 2024, Dr Cläre Tisch was the first woman in Wuppertal to be honoured with an official Women's Place NRW and recognised as a Jewish economist and committed social worker in the Jewish Women's Association,” Frambach concludes. “This form of remembrance is a sign of respect, but above all an appeal not to let the commitment of courageous women like Cläre Tisch be forgotten. The words on the memorial plaque read: 'Her life symbolises scientific excellence, social responsibility and the loss because of the persecution by the National Socialist.' The fateful course of Cläre Tisch’s life can hardly be summarised more aptly in a few words.”

Uwe Blass

Prof Dr Hans Frambach is Head of the Department of Microeconomics and History of Economic Thought at the Schumpeter School of Business and Economics at the University of Wuppertal.