World premiere - Rhapsody in Blue

Christoph Spengler / Director of the choir and orchestra of the University of Wuppertal

Photo: Sergej Lepke

"Rhapsody in Blue" - a typically American piece of music

Interview with the choir and orchestra director of the University of Wuppertal, Christoph Spengler, on the premiere of a masterpiece

No other work is as closely associated with George Gershwin as "Rhapsody in Blue". The work was announced at its premiere on 12 February 1924 with the words: "An Experiment in Modern Music". What did that mean?

Spengler: You have to realise that not only the work, but also the entire evening in which it was premiered, had this motto. Works by various composers were performed - 26 in all. I think people at the time were looking for "typically American" music that wasn't just a copy of what the great masters in Europe and Russia were creating. So there was a great deal of interest that evening, with well-known musicians attending, including Stravinsky, Rachmaninov, Stokowski, Jascha Heifetz and Fritz Kreisler. What was new about Gershwin's approach was the attempt to combine elements of jazz and classical music, which was reflected not least in the symphonic instrumentation, as it was not just a band playing, but an entire orchestra. A new style was born with "symphonic jazz", which also differed from classical jazz in that it dispensed with improvisational elements. For Gershwin, jazz was "the folk music of America" and therefore, in his view, had to be an integral part of original American art music.

At the premiere, George Gershwin himself sat at the piano, but because of the time pressure he did not even have a written-out piano score before the performance began. That was very chaotic, wasn't it?

Spengler : It really was. Gershwin was under a lot of pressure as he only had a few weeks to compose the work. He even turned down Paul Whiteman's commission to write this work at first because he was busy with other things. Whiteman then published a newspaper article in which he advertised a new work by Gershwin for the concert described above, putting pressure on Gershwin and ultimately convincing him to write the work. Gershwin was uncomfortable because he was not sure whether his skills would be sufficient to write a composition for piano and classical orchestra. So he initially produced a version for two pianos, in which he made sketchy suggestions as to which parts could be played by players in the orchestra. It was the arranger Ferde Grofé who subsequently carried out the orchestration. There was so little time before the performance that Gershwin actually only had sketchy notes in which scribbled notes such as "Wait until someone nods at you" could be read.

Gershwin's brother Ira was also involved in the work. What did he do?

Spengler : Ira and George worked very closely together - and not just on Rhapsody in Blue. Ira mainly supported George as an advisor. Specifically, the title of the work goes back to him. George's working title was "American Rhapsody", while Ira suggested the name "Rhapsody in Blue", probably influenced by a visit to an exhibition of works by the American painter James McNeill Whistler, who often gave his artworks names such as "Symphony in White" or "Arrangement in Grey and Black".

The programme booklet for the premiere of "Rhapsody in Blue" said: "Mr Whiteman (orchestra leader), with the support of his orchestra and assistants, wishes to demonstrate the enormous progress that has been made in popular music from the days of dissonant jazz, which came out of nowhere ten years ago, to the truly melodious music of today." That was jazz for a white audience, wasn't it?

Spengler: Absolutely. Jazz is clearly an "invention" of African-American musicians, originating in New Orleans around 1895. But white musicians in Dixie tried to "hijack" this invention early on. We are in the 1920s, when black jazz bands were "allowed" to play for the entertainment of whites, but a concert with Whiteman's aim was hardly what African-American musicians dreamed of. This racism continued for many years, so that even such a gifted jazz musician as Duke Ellington was not his own master, but had to become dependent on Irving Mills, who passed off some of Ellington's compositions as his own. However, George Gershwin certainly deserves credit for the fact that his later opera "Porgy & Bess" showed how enthusiastic he was about African-American culture.

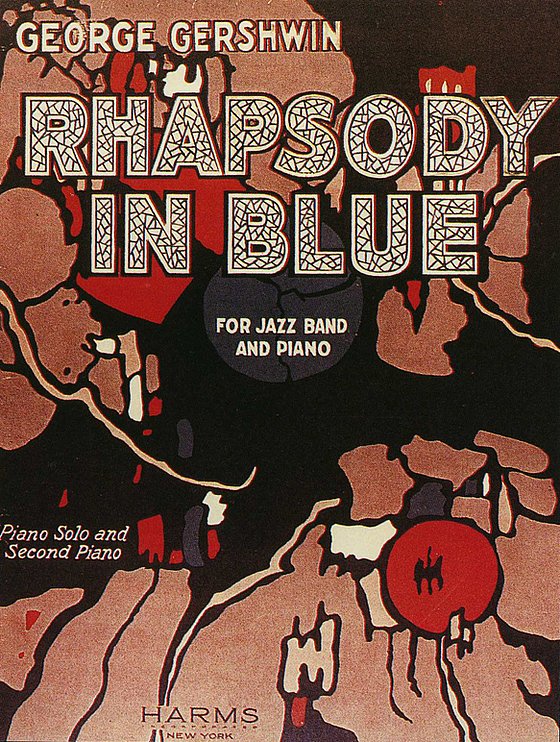

Original cover of the sheet music of Rhapsody in Blue 1924, public domain

"Rhapsody in Blue" is the juxtaposition of classical music and jazz. Was that in keeping with the spirit of the times in 1924?

Spengler : For me anyway, the question of selectivity arises. In the 1920s, "classical" music was in crisis. New composers such as Schönberg, Berg or Webern only found small, elite audiences. Their music did not seem suitable for a wide audience. Classical composers such as Stravinsky, on the other hand, do not write atonal music, but take completely different paths. In addition, people are searching for music that creates identity - especially in America. How proud people were years ago when Dvorak wrote his 9th Symphony in the USA and called it "From the New World". People celebrated that he had written a "genuine American symphony", although if you look closely, you can feel Dvorak's longing for his homeland in this symphony. I think Gershwin embarked on a highly exciting and promising path in which he tried to combine classical music and jazz. It has been a typical feature of music since the Romantic period at the latest that it carries influences from the country of its origin: Sibelius, Smetana or Grieg spring to mind. The fact that this style did not really catch on is probably also due to the fact that Gershwin's music may have appealed to too broad a mass and the educated bourgeoisie was no longer able to differentiate itself so strongly from the proletariat. The 20th century's unfortunate distinction between so-called serious and popular music has a lot to do with social demarcation. Nevertheless, other composers have also been influenced by jazz time and again - think of Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky and Shostakovich. However, I can most clearly recognise a consistent continuation of Gershwin's idea in Leonard Bernstein's compositions, which were written entirely in this spirit. For me, "West Side Story" is the consistent further development of Gershwin's ideas.

The reviews at the time were very mixed, weren't they?

Spengler: Yes, of course. And that certainly has to do with what I just said. Gershwin's music was probably just too "pleasing" for the arts pages, along the lines of "what many people like can't be art for that reason alone". It was also known that Gershwin had not dared to orchestrate the work himself, which was certainly interpreted as a weakness. Incidentally, he responded to this accusation in a marvellous way by presenting works such as "An American in Paris", his "Piano Concerto in F" and finally his opera "Porgy & Bess", which are magnificently written for orchestra. Gershwin's genius was very obviously misjudged. A meeting between Alban Berg and George Gershwin is a nice contrast to this. Gershwin was very interested in new music, and Berg played him his "Lyric Suite" on the piano, a strictly atonal piece. Berg then asked, "And now play me your 'Rhapsody in Blue'!". Gershwin was unsure: "Now, after the Lyric Suite?". Berg responded: "Music is music, Mr Gershwin, and now play it!"

George Gershwin is also known as the pioneer of the 'Third Stream'. What does that mean?

Spengler : "Third stream" - a term introduced by the American musicologist Gunther Schuller in the 1950s - refers to the attempt to overcome the stylistic difference between improvised jazz and fully composed "serious music" and to achieve a fusion of these two genres. Of course, this idea was not new, as composers such as Debussy, Ravel and Milhaud had already utilised elements of jazz in their compositions. I think you could say that Gershwin approached this direction "from the other side". He came from light music, from Broadway, and endeavoured to find an American art music of his own character. Incidentally, this went so far that Gershwin asked the French composer Maurice Ravel if he could give him composition lessons, to which Ravel replied: "Oh, better be a good Gershwin than a bad Ravel." Gershwin did not see jazz as an interesting touch to freshen up classical harmony and rhythm, but as genuine American folk music and therefore an essential component of American art music. And so his works are very clearly in the spirit of the "Third Stream".

You have also played "Rhapsody in Blue" with the Bergische Universität Orchestra. What fascinates you about this work?

Spengler: Very simple: I love Gershwin's music! And it's this symbiosis of jazz that really fascinates me. I think it's absolutely brilliant to utilise the incredible tonal diversity of a symphony orchestra for this. And what Gershwin wanted, he achieved for me: to write great, genuinely American music. In my opinion, what he created was something really new, but it didn't frighten the audience like some so-called "new music" compositions, but rather played its way into people's hearts. And that is exactly what drives me again and again in all the music I choose for my ensembles: It has to be music that moves us, that takes us out of our everyday lives and allows us to be completely absorbed in the sound. This is exactly what Gershwin achieves with his marvellous "Rhapsody in Blue".

Uwe Blass

Christoph Spengler studied church music in Düsseldorf. He took over the direction of the university choir in 2007 and the orchestra in 2011. In 2016, the rectorate awarded him the University of Wuppertal's Medal of Honour. In 2017, he was appointed church music director by the Protestant Church in the Rhineland.