First Winter Olympics in Chamonix

Torsten Kleine / Working Group "Integrative Theory and Practice of Sport"

Private photo: Torsten Kleine in the Olympic Stadium in Barcelona

"The first Winter Olympics were actually an International Winter Sports Week"

The sports scientist Torsten Kleine about the first Winter Olympics in Chamonix (France) in 1924

Mr. Kleine, the first Winter Olympics took place from 24 January to 5 February 1924 in Chamonix, France. Compared to today's Winter Games, the competitions back then still had the magic of imperfection, which we can smile about today. For example, the ice rink had turned into a lake shortly before the opening ceremony due to a thaw and only a sudden drop in temperature saved the competitions. What else made the games different from today's synchronised competitions?

Kleine : Many people are familiar with the motto "higher, faster, further" that we associate with the Olympic idea, and perhaps that's a good place to start, because a lot has changed enormously - a lot has become faster, higher and further. In 50 km cross-country skiing, the men run twice as fast today as they did back then in Chamonix. In ice hockey, Canada dominated the competitions with a goal difference of 110:33. Today, the performance density is much higher and Canada doesn't always win. A lot has changed in the sporting arena. Back then, five people were allowed in the four-man bobsleigh, but that has not been allowed for a long time. When they carried the bobsleigh to the runway back then, athletes still smoked a cigarette, you can see that in old pictures. Back then, there was only one telephone line from Chamonix to Switzerland, which the reporters had to share. That's unimaginable in today's media world. But on the other hand, you can also see that not everything was different, because even back then, the organisers were tasked with ensuring that their sports venues would remain available for at least another thirty years. That was already an aspect of sustainability that we are thinking about again today. And the question of infrastructure and development is also being discussed today, including in Germany when considering whether to bid to host the event again in 2036 or 2040. Back then, a railway station was built in Chamonix for the Games and the railway company was also immortalised with a small logo on the poster. These are the first signs of sponsorship, and the construction also had positive effects for tourism. The political dimension that the Olympic Games have had throughout his life was also evident at the time. Germany was not allowed to take part because the French occupation, which extended into the Bergisches Land region, was an issue and reparations were not paid.

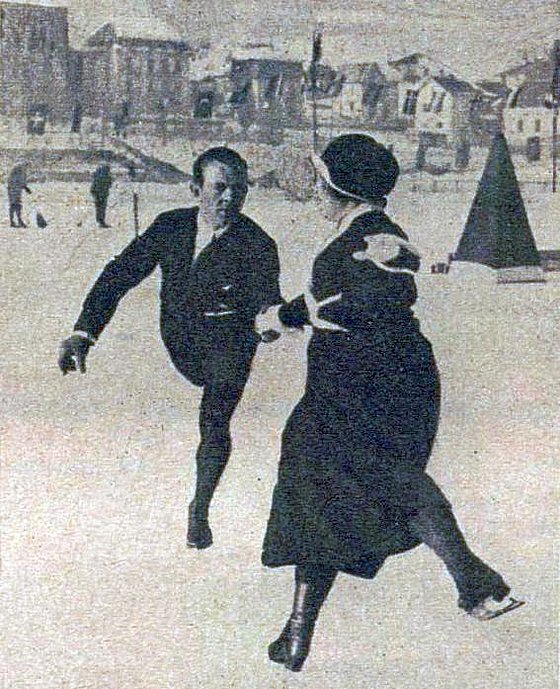

Alfred Berger and Helene Engelmann, Austrian Olympic figure skating champions in 1924, public domain

It is curious that figure skating, for example, was introduced by the Olympic Committee in the summer of 1908, even though there were no Winter Games yet. Why did the IOC quarrel with itself and raise the Olympic flag in 1924, but forbid the lighting of the Olympic flame?

Kleine: The 1924 Olympic Games were initially not the Olympic Games. In 1924, the modern founder of the Olympic Games, Pierre de Coubertain, was still IOC President. He didn't actually want a Winter Olympics and was against it. There were other events in Scandinavia that also had something against it and so there was actually an International Winter Sports Week under the auspices of the IOC, but not officially the Olympic Games. This title was only awarded a year later by the IOC at a meeting in Prague. But there were Olympic symbols on site. The Olympic flame did not exist back then. It wasn't invented until 1928 in Amsterdam. The torch relay was not even introduced until 1936 in Berlin. The Olympic flag, however, flew in Chamonix in 1924. Coubertain had invented it himself for the 1920 Games in Antwerp.

The disciplines also included bizarre sports such as the military patrol run. What was that?

Kleine : The connection to the military, war and combat is familiar from the history of sport. This is something that accompanies sport, and back then there was this discipline where the athletes - there were four men - competed as a group with skis, uniform, rifle and rucksack. There had to be one officer and three other soldiers. They then ran on skis and after half of the 30 kilometres, they shot at targets that were 250 metres away, much further than what we know today. They got bonus seconds for this. It took them about four hours with bag and baggage. In 1960, biathlon was included in the Olympic programme as a further development.

An 11-year-old Norwegian girl made a name for herself back then, who really came out a few years later. Who was that?

Kleine: If the press is to be believed, Mrs "Hoppla" initially attracted attention because she was very young, namely 11 years old. She fell on her bum during her figure skating performance and is said to have shouted "Hoppla" and came last out of eight participants. Sonja Henie from Norway then attracted attention because she won the next three Olympic Games. She then went to Hollywood in 1936 to pursue a film career. There she was one of the best-paid actresses ever. Other athletes did the same, such as Johnny Weissmüller, Olympic swimming champion in 1932, who became known as the film Tarzan. She, on the other hand, made a career in film with shows that also had to do with figure skating, but is still considered one of the most successful figure skaters in the world today.

An athlete had to wait 50 years to receive his bronze medal. What happened?

Kleine: An incredible amount has changed in terms of the rules and data management. The example in the question is about ski jumping. The jury had simply miscalculated. After fifty years, Anders Haugen, who actually came third, was personally presented with the bronze medal by the daughter of the third-placed skier. Another story that also took place in 1924 is that of curling. There were winners there too, but they did not receive a medal because it was supposedly a demonstration competition. This was only realised 82 years later. In 2006, the gold medal was actually awarded to the British winners posthumously at the Olympic Games in Turin because it could be proven that it had been a regular competition at the time.

At the time, 245 men and 13 women competed for their medals in a total of 16 disciplines. How extensive is the sports programme today?

Kleine : Back then there were 14 disciplines in 9 sports and today there aren't that many more sports. There are 16 sports planned for 2026, but there are 116 disciplines. You can see how the number has developed over the years. You can also see from the number of participants that the gender ratio is changing. Most recently in Beijing 2022, there were 1,600 men and 1,300 women from 92 countries. At the 1924 Winter Games, only 16 countries were involved, while at the Summer Games in Paris this summer, athletes from almost all of the world's more than 200 countries are expected to take part. This also shows the global significance of the Games. Over 3,000 athletes are expected to take part in Turin in 2026.

Many things have changed and new disciplines are constantly being added. For example, ski mountaineering will become an Olympic discipline in Milan and Cortina d'Ampezzo in 2026. What is it and where does it come from?

Kleine : In German, ski mountaineering is referred to as ski mountaineering or ski touring. Internationally, it is often simply referred to as skimo. There has also been a development that can be found in many sports. An idea for exercise is developed, discovered, invented and initially practised as a leisure activity. And then there are people who want to turn it into a competition. Then rules are drawn up and people think about how to do it. The Italians in particular have campaigned for it to become an Olympic sport, as it is very popular there. The idea is that you ski and run through open terrain, there are inclines and you have to run certain routes and ski others on open terrain. There are now even rules about how much and what clothing you can wear.

The Olympics stand for big games, big entertainment, big emotions, and this also applies to the construction of sports facilities. In the course of the sustainability debate, however, we must also ask how it is possible to organise the Olympic Games in times of environmental protection, climate crisis, sustainability and immense costs so that they are not just a cost-intensive extravagance. So in your opinion, are two-week Olympic Games a legacy or rather a legacy?

Kleine: This is by far the most difficult question for me. I'll try to answer it in three ways. Firstly, regarding the construction of sports facilities: if you look at the 2018 Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea, you realise that the Olympic Stadium, which was only built for the opening and closing ceremonies, no longer exists. A stadium for 35,000 people was built for just two events, which cost almost 100 million euros and is no longer there. In 2026, the closing ceremony will take place in the Arena di Verona, built in 30 AD, which still exists and is used for many events. The opening ceremony will take place in the stadium in Milan, which was built in 1926. This shows very clearly that there are also more sustainable options. The Olympic Games have a global power of steel and Italy shows that these events can also be organised sustainably in the 21st century in order to at least reduce reservations.

The second answer relates to the Olympic idea. Coubertain tried to bring the modern Games back to life in order to bring people together again and create peace. Historically, the Olympic Truce has always had an effect in ancient times. In the modern era, connections and relationships were formed between athletes from different nations, even genuine friendships such as the one between Jesse Owens and Lutz Long in 1936 as a prominent example. Conversely, this idea has also been changed, commercialised and used politically. If you look at the discussion about the exclusion of nations that are involved in acts of war, then the handling of the Olympic idea is at the centre of society. Sporting successes have also often been used politically and one can ask oneself whether public money should be used for this. The IOC undoubtedly earns very large sums of money from this event and, just like a hundred years ago, is still a very elitist clique that calls the shots and does not necessarily make decisions democratically. On the other hand, the IOC also supports sporting projects worldwide that would otherwise not be possible. It is therefore very ambivalent.

And the third answer is very personal. I thought for a long time about travelling to the Olympic Games myself as a spectator and decided to give it a try for Paris this year. I actually got tickets for it. When I think about how much energy is needed there for the stadiums, the competitions, the travelling of athletes, officials and spectators etc., it's clearly a double-edged sword. But I will perhaps be able to give a definitive, personal answer when I am back. I think that my experiences there can then also benefit the students in my seminars.

Uwe Blass

Torsten Kleine is a research assistant in sports science (working group "Integrative Theory and Practice of Sport") at the University of Wuppertal.