Wallpapers: Contemporary witnesses of fashion history

Prof`in Dr. AnneMarie Neser / Design and Art

Wallpapers are contemporary witnesses of fashion history

The first wallpaper museum was opened in Kassel in 1923. Prof`in Dr. AnneMarie Neser from the Faculty of Design and Art on the long tradition of wallcovering

On June 30, 1923, the first German wallpaper museum was opened in Kassel. How long have wallpapers actually been around?

Neser: Wallpaper as we know it today has probably been around since the Renaissance. But the term wallpaper was already used in ancient texts, although it was mainly used to describe wall hangings, tapestries and wall decorations of various kinds. I'm always fascinated by the fact that since time immemorial there has been a need to decorate intimate living areas, because you can actually interpret Stone Age carvings in this way, someone has designed his interior in a dark cave.

What is so special about wallpaper, about these testimonies of living culture?

Neser: Wallpapers are indisputably a valuable cultural asset and of great importance for interior design. They provide a glimpse into private rooms and also show who could or was allowed to afford some precious items. Wallpapers are also witnesses of technical development. Take, for example, the continuous paper used for wallpaper; it would not have been possible without the invention of the circular screen around 1830, a first step towards the industrial production of wallpaper, which then also resulted in lower prices. If you look at wallpapers from different times, you can take a time travel through the life and living cultures of the centuries. Wallpapers, like so many things, are subject to the change of fashions of the time. They can pick up changes very quickly and through their interchangeability reach a large circle of people.

What did wallpaper look like in the 1920s and 1930s?

Neser: Here we are in a time when objectivity and reduction are rampant. The ornamental richness of the 19th century is losing its significance and is even being severely criticized. Skilful became fake, imitation is considered dishonest, only the genuine has value. One knows the lecture title of the Viennese architect Adolf Loos 'Ornament and Crime`. Loos lamented the superficial ornamental decoration from the point of view of wasted working time.

The wallpapers then also show matter-of-factly strict, rather geometric patterns or are plain colored; they combine with the wall surface. Monochrome surface patterns gain in importance. Color harmonies determined the atmosphere of the rooms.

The large social building projects of the Weimar Republic changed the attitude towards wallpaper, also with regard to rationalization in the building industry. Wallpaper was quicker to apply than hand-made wall painting. On a large scale, wallpaper was used, for example, in the Frankfurt housing development (Neues Frankfurt).

The most popular wallpaper collection of this period was the Bauhaus, it came on the market in 1929 with different patterns such as grids, lattices or dashes. In the basic idea, it is a transfer of the surface effect of plaster on paper. Bauhaus wallpaper was developed by the Workshop for Wall Painting under the direction of Hannes Scheper and is still produced today.

In retrospect, fashions or also styles like to be presented in a clearly distinguishable sequence, but actually there is no such thing; styles, fashions always interpenetrate each other for a certain time before they prevail and replace each other. In the first third of the 20th century, one can therefore find Art Nouveau wallpaper, for example, in the style of Henry van de Velde, next to sober, simple patterned wallpaper of the Bauhaus or the Wiener Werkstätten.

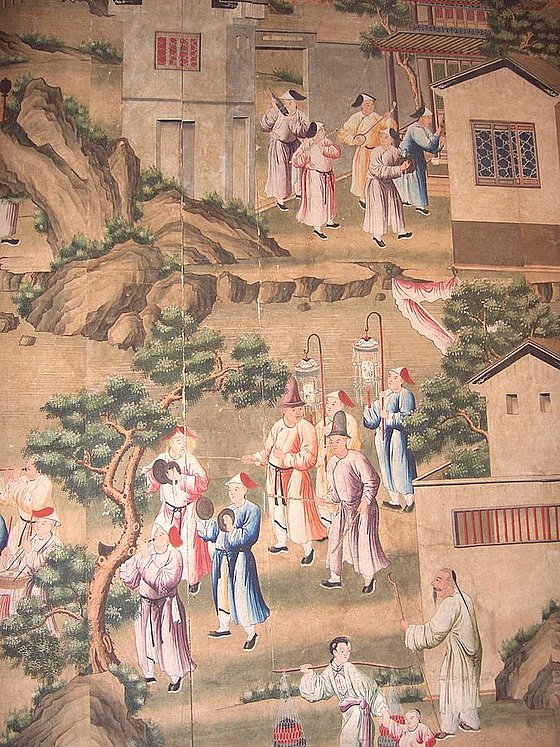

Chinese wallpaper showing a funeral procession; Qianlong period, ca. 1780

German Wallpaper Museum, Kassel

Photo: Dr. Meierhofer

What materials did you use on the walls?

Neser: If you go through history, there were all kinds of things, such as leather wallpaper from the late Renaissance and the Baroque, then fabrics such as damask, brocade, velvet, silk, also oilcloth wallpaper, and then paper. This, by the way, was used earlier than is generally thought. In Switzerland, there are surviving sheets of paper on walls and ceilings from as early as the 15th century. From the 1970s, we also know cork wallpaper, rattan, cardboard, all sorts of things came to the wall. Today, imitations of building materials, such as concrete, stone can be seen, so the range is inexhaustible.

Many wallpapers did not always meet the taste of their viewer. The last words of the writer Oscar Wilde, before he died in his Paris hotel, were: "Either this hideous wallpaper goes - or I do. " Today, wallpaper or even paint in hotels or public buildings is usually monochromatic. Is that chic or boring?

Neser: Wallpaper, like many other things, can be seen as a matter of taste, especially if the assessment is made from a personal point of view, as was the case with the writer Oscar Wilde, who was known for his exquisite taste of the times. But from a professional point of view, it's not a matter of whether I personally like a paint job or a wallpaper better. Rather, the focus is on what you want to achieve with and in the room, for example, should the room radiate calm or stimulate activity, who uses the room, etc. It is about creating the appropriate framework for the planned use with the appropriate materials. It is always the question, in which context do I design, it is about an atmosphere that I want to create in the room. It is a composition of various elements. For example, the use in a hotel means more wear and tear, the rooms are used more intensively than private rooms. Consequently, hotel or even hospital designs have completely different requirements than private homes.

After the closure of the Wallpaper Museum in 2008, the valuable exhibits were restored for a permanent exhibition and will be on display again from 2025 in a 29-million-euro new building of the present Hessian Administrative Court opposite the State Museum. In the new permanent exhibition, which will cover approximately 1,500 square meters, visitors will be taken on a journey through 600 years of interior design history. How has the wall decoration changed over the centuries?

Neser: The answer to this question could actually fill books. Roughly speaking, we know interior designs from very early times, but in relation to the Wallpaper Museum, I would start with the Renaissance period. There are these famous gold leather wallpapers, which, of course, you always have to imagine with the lighting of the time, this special glow in the glow of candlelight. Gold leather wallpapers are by the way not at all made with gold, but the leather was treated with a special resin. These wallpapers were very expensive and a status symbol. On the other hand, those who could not afford gold leather wallpaper used fabric coverings for the wall: brocade, damask or silk. In France, however, fabric wallpaper was the preserve of the nobility, so that by 1700 middle-class households were switching with great interest to the newly developed paper wallpaper. The British, in turn, who still have a great wallpaper tradition today, were quick to introduce a paper tax at the time to capitalize on the newly awakened wallpaper-buying frenzy among the bourgeoisie. In the 18th century, it was also en vogue to furnish rooms with Chinoise-style wallpaper. This was less something for private homes and more for intimate retreats of the aristocracy, such as garden pavilions or tea rooms. The fashion was based on Chinese models, inspired by travel reports and also the widespread enthusiasm for Asian luxury goods. The 19th century then knows the valuable hand-printed panorama wallpapers in the salons of wealthy citizens or aristocrats. City views, landscapes or mythological dramas expand here the room impression; very exclusive, but high expenditure and enormous price.

The more than 23,000 objects are also to be made accessible virtually via an online catalog. This includes, among other things, design of the 70s, which is again highly modern. An outsourced show demonstrated the particular influence of Pop Art on the wallpaper tradition. What colors and patterns were dominant back then?

Neser: They were patterns and colors inspired by current art movements, such as Op or Pop Art, which were shown at the same time at the documenta in Kassel in 1968. You might know the wallpaper with the cow by pop artist Andy Warhol or the Nana wallpaper by artist Niki de Saint Phalle. The patterns were colorful, loud, sometimes garish and had those psychedelic patterns that could be exhausting in a room. The color range included orange, sunny yellow, a powerful tomato red, olive green and also deep brown, often a black as a contour line.

Wuppertal also has a unique wallpaper tradition. The woodchip wallpaper was developed by Hugo Erfurt in 1867 and is now one of the German "brands of the century". In the 8th generation, Erfurt sells innovative, design-oriented and ecologically sustainable solutions for wall design in addition to woodchip products in over 30 countries worldwide. How important are wallpapers for interior design?

Neser: If you take woodchip alone, which is probably very popular in Germany - I think we are the No. 1 woodchip country - wallpaper is an important wall design option. Woodchip wallpaper is robust, inexpensive and easy to apply. It established itself in the 1920s and in the 1980s was perhaps also a quick alternative for the garish patterns of the 1970s. I myself have used it many times in my student apartments; old apartments with cracks, bumps, holes in the walls, the woodchip helps immensely. It's a great way to even out unevenness. With the right paste, it was perfect.

Overall, wallpaper is an important means of interior design. Wallpaper can enliven a room, highlight a wall, cover something up, emphasize components or surfaces, or make a room larger or smaller, depending on what patterns or color combinations you use. Wallpaper can give the room a special character. It is important as a historical and design phenomenon in the whole range of possibilities we have in this field.

Uwe Blass

Prof`in Dr. AnneMarie Neser received her doctorate from the Faculty of Architecture at the University of the Arts in Berlin with a thesis on Prussian monument preservation. Since 2007, Prof. Neser worked as a lecturer at the Zurich "House of Color", whose Berlin branch she headed from 2010. From 2014 to 2017, she was a research assistant at Bergische Universität in the department of Didactics of Visual Communication as well as coordinator of the interdisciplinary educational platform "color. education". Since winter semester 2018, she has been a professor of building culture and spatial design in the Faculty of Design and Art in Wuppertal.