1925 World Exhibition in Paris

Prof Andreas Kalweit / Industrial Design

Photo: UniService Third Mission

The style of an aspiring, modern society

The locksmith, engineer, industrial designer and entrepreneur Prof Andreas Kalweit on the world exhibition in Paris 100 years ago

What innovations were on show at the 1925 "Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes" in Paris?

Kalweit : The international world exhibitions - the first was in London in 1851 - had established themselves as technical and craft exhibitions during the period of industrialisation. The World Exhibition in Paris in 1925 was a milestone for modern design after the First World War and showcased a multitude of innovations in both aesthetic and technological terms. Above all, it showed the evolving change in design from arts and crafts to industrial aesthetics, from ornament to formal discipline.

The pavilions at the exhibition were ultra-modern in design. As an architect, Le Corbusier caused a sensation with his cubist pavilion, a radical break with the previously decorative character of the exhibition. Art Déco as a stylistic, luxurious innovation was presented to the general public for the first time. The furniture designer and interior decorator Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann presented luxurious furniture with fine veneers and classicist forms. The first streamlined automobiles were shown.

The designer and painter Sonia Delaunay-Terk integrated abstract, rhythmically coloured patterns into textile designs. The exhibition presented innovative technologies, industrial production methods and innovative materials, including Bakelite.

It thus set the style for the following decade and had a lasting influence on both European and American designers.

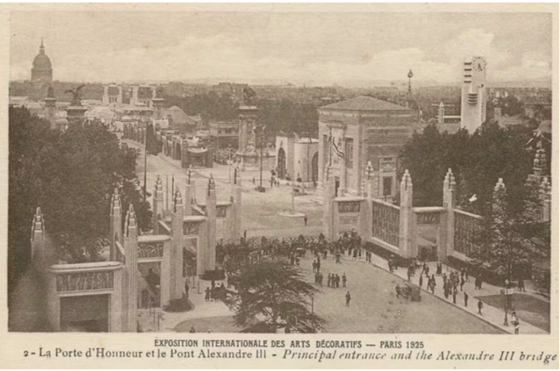

The main street of the exhibition, from the Porte d'honneur and the Pont Alexandre III to the Invalides, 1925

Photo: public domain

The "Art Deco" style is also named after the world exhibition in Paris. What is meant by this?

Kalweit: Art Deco refers to a design style that emerged in the 1910s and reached its peak in the following two decades. The 1925 World's Fair in Paris was the first time the style was presented on a large scale and given its name.

Art Déco developed as a reaction (counter-trend) to the ornate Art Nouveau style and was characterised by its geometric shapes, symmetry and order, luxurious materials such as precious woods, marble, chrome and glass and the influences of new production techniques.

Art Deco was the style of an aspiring, modern society that wanted to combine elegance with progress. The style characterised design, architecture (the famous Chrysler Building in New York), fashion and art worldwide. It is still recognisable today in product design, graphics, fashion and architecture - as an expression of urban sophistication, refinement and dynamism.

Poster World Exhibition

Photo: public domain

The new products presented included plywood furniture, porcelain and fashion. The new style was to be decorative, but above all it was to be used. Plastics and chrome-plated metals were added from industrial design? These were also used in the kitchen appliances of the time, weren't they?

Kalweit: That's right. These are central aspects of Art Deco aesthetics and functionality - especially with regard to the combination of aesthetic appeal and practicality. The 1925 exhibition was not just a showcase for luxurious individual pieces, but also presented the practical application of modern materials and production methods in everyday life.

Important designers increasingly turned away from Art Nouveau and emphasised functional, modern product forms that met the new production processes and economic requirements (Gerd Selle; Geschichte des Design in Deutschland, 1994). While the Art Nouveau was still characterised by floral, curved and decorative decorative elements for old sewing machines or household scales, for example, they were replaced by the new design language of Art Deco.

New materials such as Bakelite, one of the first plastics, were used for the serial production of lamps, radios, light switches and housings for kitchen appliances. Chrome-plated metals were used for toasters, kettles and furniture frames and looked particularly elegant and hygienic. Plywood was a modern and inexpensive material for light and elegant furniture. My great-grandfather from our traditional family business had also registered property rights for the production of marzipan moulds made of Bakelite.

Modern materials and technologies were combined with suitability for everyday use and style. This was particularly reflected in the design of everyday objects and furniture, which were functional, elegant and often industrially manufactured - an anticipation of modern industrial design, which is still taught and practised at our university of Wuppertal today.

Vacuum jug "No. 24 Jug"

Design: Reinhold Burger, 1925, Thermos Ltd, London (GB), Bakelite

Photo: Schriefers Design Collection

Here in our Schriefers design collection at the university of Wuppertal, we also have various examples from this period. For example, there is a model of the Frankfurt kitchen, which is said to have a high design standard. How can you recognise that?

Kalweit: The Frankfurt kitchen was a milestone in the history of design and architecture because it embodied a radically new understanding of living and working space design and, above all, with a thoroughly functional design standard that was far ahead of its time.

The kitchen was not designed as a representative room, but was functionally rationalised like a workplace - inspired by industrial production processes and railway dining cars. All the necessary movement sequences were optimally thought out and the surfaces were easy to clean. The design was therefore not an end in itself, but combined function and aesthetics to a special degree. The design was therefore above all a solution to a problem rather than just decoration.

Frankfurt kitchen

Photo: Schriefers Design Collection

Art Deco was also inspired by the German Bauhaus. How can this be established?

Kalweit : The statement that Art Deco was also inspired by the German Bauhaus is only partially true. As far as I know, Bauhaus was not a direct predecessor of Art Déco, but rather a counter-design that existed at the same time. Both Bauhaus and Art Deco combined art, craftsmanship and design. While the Bauhaus focussed on functionality, reduction and social reform, Art Déco stood for luxury, decoration and elegance. Both shared an enthusiasm for the modern, the industrial and the new - which is also reflected in some formal parallels.

At the World's Fair, modern pavilions were seen for the first time that followed the geometric, clear design language of the Bauhaus.

Chair "B403", so-called "Kramer chair"

Design: Ferdinand Kramer, 1927 ,Gebr. Thonet A.G., front and plywood

Photo: Schriefers Design Collection

When did the style lose its significance?

Kalweit : The Art Deco style lost its international significance from the mid-1930s, with the onset of the global economic crisis from 1929. Luxury, glamour and urban optimism no longer fitted into a time of economic hardship. Most Art Deco products were lavish and expensive, and the general public simply could no longer afford them.

The rise of fascist regimes and the transition to totalitarian structures displaced the Art Deco style at different times, depending on the country. So the style did not suddenly disappear.

However, Art Déco experienced repeated revivals - in the 1960s, 70s and 80s largely as a reaction to overly reduced, functional designs. Today, Art Déco still stands for elegance, craftsmanship and visual opulence. Even today, parts of the style are adapted, as so many styles are quoted that offer stability and familiarity, especially in uncertain times.

Uwe Blass

Andreas Kalweit studied mechanical engineering at the Niederrhein University of Applied Sciences after completing an apprenticeship as a fitter and then industrial design at the University of Essen, graduating from both programmes with a diploma (mechanical engineering with distinction). Since 2012, he has been a professor of "Manufacturing & Material Science - specialising in construction technology and systems in design" at the University of Wuppertal.