Josephine Baker in Paris

Marie Cravageot / Romance Studies

Photo: Jan Wengenroth

Josephine Baker in Paris

Marie Cravageot on a true star of the Roaring Twenties

The child of a washerwoman became an "idol of dark steel", said the artist Jean Cocteau about the American Josephine Baker, who drove the whole of Paris crazy from 1925 onwards. How did she end up in the French capital in the first place?

Marie Cravageot: Josephine Baker, whose real name was Freda Josephine Macdonald, was born in 1906 to a black mother and an unknown, probably white father in Saint-Louis in the US state of Missouri, a state that was particularly characterised by racial segregation. Until the age of four, she was raised by her grandmother, who had been a slave. She took an early interest in dance, but in order to help her family, she had to work as a housemaid for rich white people. At the age of 13, she was married off to a violent man who beat her. After hitting him on the head with a bottle in defence, she divorced him and remarried at the age of 15 under the name Baker. Josephine joined a travelling dance group, which took her to New York. She appeared on Broadway in Shuffle Along, the first black show to be performed in halls reserved for whites and in which black audience members were given a seat in the stalls. In the summer of 1925, she was discovered by Caroline Dudley Reagan, who was looking for a star for a musical, the revue Nègre, which she wanted to perform in Paris at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées.

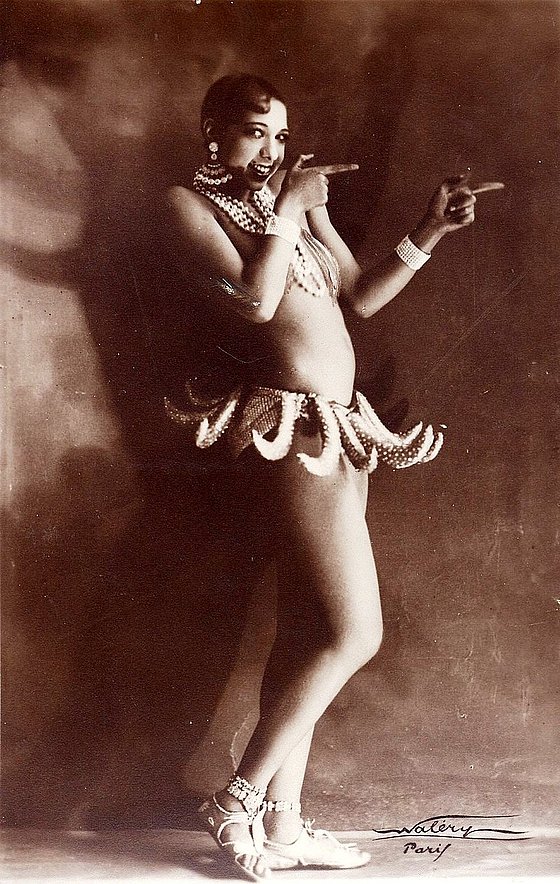

Josephine Baker in the attitude of a burlesque showgirl, 1927

Photo: Ders.

On 2 October 1925, Josephine Baker performed for the first time in Paris in the "Revue Nègre" at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Her performance was a sensational success and made her a star overnight. She moved wildly and animalistically, virtually naked to jazz music. With her famous dance in a banana skirt, she also brought a new dance to Europe. Which one?

Marie Cravageot: Josephine Baker came to France during the cultural and artistic heyday of the Roaring Twenties, a favourable environment for her career. She and her troupe travelled to the French capital on 25 September 1925 on the Berengaria, a transatlantic liner that covered the New York-Cherbourg route. Rehearsals began shortly after their arrival. On 2 October 1925, she appeared in the first part of the Revue Nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées and quickly sold out the house. Almost naked, dressed only in a simple loincloth and artificial bananas, she danced Charleston in front of a savannah backdrop and to the rhythm of the drums. There, she interpreted a painting entitled La Danse sauvage (The Wild Dance) and said: "This is about making fun of white people and their way of managing the colonies, because although France is less racist than the United States, it still has progress to make in terms of people with a different skin colour and their integration into society!" For her, this journey was a liberation. She said: "One day I realised that I was living in a country where I was afraid to be black. It was a country that was reserved for white people. There was no place for black people. I was suffocating in the United States. Many of us left, not because we wanted to, but because we couldn't take it anymore.... In Paris, I felt liberated."

Josephine Baker ridiculed these clichés by making faces and adding comic elements to the choreography. With her extroverted dance style and her presence, she brought jazz dance and other new dance forms to European theatres and variety shows. She became a real star of the so-called Golden Twenties.

She was regarded as the epitome of the Roaring Twenties. Why?

Maire Cravageot: Josephine Baker embodied the "Années folles" (the Roaring Twenties) as an aspiring sex symbol and celebrated dancer who popularised jazz dance in Europe. With her exotic image, daring outfits and scandalous appearance, she epitomised the new beginnings and permissiveness of the era, while her career began in France after racist experiences in the USA.

Baker popularised jazz dance in Europe with her performances in Paris, Berlin and other cities, shaping the vibrant culture of the Roaring Twenties. With her image as "Black Venus", she consciously catered to the expectations of the public and embodied the exotic charisma and burgeoning permissiveness of the time. Her dance style is known for its fast, synchronised movements and its energetic character of the "Golden Twenties".

She perfectly epitomised the Golden Twenties in France thanks to her innovative performances, which made her an icon of vaudeville and the rise of "Negro" fashion and culture, of which she became a symbolic figure. The theme of "Negro culture" inspired the avant-garde at the beginning of the century, before it materialised in the figure of Josephine Baker and the arrival of jazz on the Parisian stage. The first "Negro" dance was introduced in 1903 by Gabriel Astruc at the Nouveau Cirque in Paris: It was the Cake Walk, inspired by the American minstrel shows in which white people dressed up as black people to sing and dance like the former slaves.

The "art nègre" (black art) that was so dear to Picasso and the surrealists, the poems of Cendrars or the melodies of Milhaud and Satie bear witness to a certain "Negrophilia" of French artists in the first quarter of the 20th century. It was inextricably linked to a quest for modernity that caused a scandal: African idols in contrast to the statues of classical antiquity, jazz, which arrived with the American soldiers of the First World War and competed with the chamber music or opera of old Europe - and finally Josephine Baker, the spirited dancer in the light banana skirt. It seems that the "wild dance" with which the dancer presented herself to the entire Parisian audience on 2 October 1925 was included in the New York production at the request of the owners of the Music-hall des Champs-Élysées, who were short of spectators. She embodied the image of the emancipated woman who was able to make decisions about her body - to indulge in the celebration of the wild years.

Josephine Baker in a banana skirt from the Folies Bergère production Un Vent de Folie

Photo: Ders.

She loved and lived the image of the wild Amazon and walked through Paris with a live leopard. Was that the chic of Art Deco?

Marie Cravageot: The seductive, instinctive Josephine Baker was the favourite of the whole of Paris. She owed this in particular to Henri Varna, the director of the Casino de Paris, and the musician Henri Scotto, who wrote her greatest success in 1930: J'ai deux amour . The same Varna gave her a cheetah called Chiquita, who accompanied her on stage and in private. She walked him on a lead in Deauville or on the Champs-Elysées, dressed in a spotted dress or a fur coat. With him, she became a real "celebrity". She inspired the fashion of the time: fashion designers sketched her silhouette, women copied her short hairstyle, the strands of which were glued to her forehead with gel. A cut that has since been known as baby hair. From an exotic curiosity, she became a star.

At this time, when Josephine Baker was becoming the muse of haute couture, starring in films with Jean Gabin and travelling the world with her animals - cheetahs, pigs, goats - she also spent a lot of time in a famous brasserie in Paris, La Coupole, with its extravagant Art Deco décor. In the 1930s, this was an important meeting place for the artists of Montparnasse. She spent so much time there that the painter Robiquet immortalised her on one of the brasserie's painted columns.

In 1951, she toured America. For the first time, there was no racial segregation at her performances. She was therefore the first entertainer to be allowed to perform in front of a mixed audience. That was a sensation, even though she was banned from entering the USA until 1963, wasn't it?

Marie Cravageot: After years of absence, Josephine Baker returned to the United States in 1948 for a singing tour, which turned out to be a nightmare. In New York alone, she was refused more than thirty hotel reservations because of the colour of her skin. Racial segregation was so strong in post-war America that there was a travel guide, the Green Book, to help African-Americans move around freely. A significant event occurred a few years later when the Copa City Club in Miami invited Josephine in 1951, but she refused to sign contracts with theatres that practised racial segregation. She managed to persuade the venue to open its doors to African-American audiences and, as a testament to the artist's popularity, these unprecedented conditions were accepted in the United States. She was the first artist to perform in front of a mixed audience.

However, her political engagements were controversial in the press, which had an impact on her career in the United States. In the 1960s, the March on Washington and her visit to Cuba under Castro led to her visa being revoked several times. In 1963, Josephine Baker even held her press conferences in French, accompanied by a translator. She did not give up her convictions in favour of her artistic career. Her modernity lay in overcoming boundaries, utilising institutional constraints and then freeing herself from them. She was less an activist inspired by a particular ideology than an independent fighter. Her concerns corresponded to her own life experiences.

In France, however, she was much more than a dancer. During the Second World War, she was involved in the Resistance, obtained her pilot's licence, adopted 12 children in the 1950s and thus set an example against racism. Martin Luther King even invited her to speak at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. How political was she?

Marie Cravageot: After her marriage in 1937, she became French, and her career and life took a different turn during the occupation. When war broke out, Joséphine used her fame and talent to motivate the troops at the front. She became involved with the Red Cross, sent parcels and even became godmother to more than 400 soldiers. After General de Gaulle's appeal on 18 June, she was "approached" by Jacques Abtey, the head of military counter-intelligence in Paris. He suggested that she secretly collect sensitive information from the enemy. Again, she used her fame and charm to visit the Italian and Portuguese embassies in particular and gather information on the positions of the occupying armies. Thanks to her fame and her travelling, she was able to gather information and pass it on to the Allies. Among other things, she used sheet music as a carrier for her coded messages. In 1943, Joséphine travelled to North Africa, still with the aim of boosting the morale of the troops. She also supported the French army financially by handing over all her wages. From 1944, she joined the air force as a lieutenant and was one of the troops that landed in Marseille in October. She was later awarded the Resistance medal, the War Cross and the Legion of Honour for her actions.

Joséphine Baker was also committed to freedom and against racism and was a caring mother to the twelve children from all over the world whom she adopted after the war together with her husband Jo Bouillon. A victim of discrimination in New York in 1951, she supported the emerging civil rights movement and was one of the few women to give a speech at Martin Luther King's famous March on Washington in 1963, wearing her resistance fighter's uniform for the occasion. In this speech, she emphasised the importance of dignity and freedom for all and contrasted her experiences of discrimination in the United States with the freedom she had found in France. She also encouraged young people to go to school and arm themselves with a pen rather than a gun, claiming that "a pen is mightier than a sword". Finally, she emphasised that unity is essential for victory and that efforts must be redoubled after this historic day. Her speech, eagerly awaited by the crowd, was seen as the culmination of her life as a fighter and strengthened the hope for a reconciled world, as she herself said, because it was the best day of her life.

One of the strong symbols of Josephine Baker's humanism is her "Tribu arc-en-ciel" (Rainbow Tribe) of adopted children from different backgrounds, with whom she wanted to create a living example of worldwide brotherhood. She took in these children from all over the world, of different ethnicities and religions, in her castle Les Milandes to show that it is possible to bring people together as an example of universal brotherhood. She wanted the children to set an absolute example of tolerance to the adults.

Baker as a sous-lieutenant in the French Armée de l'air, 1948

Photo: Ders.

She died 50 years ago and was buried in Monaco. In 2021, she will be posthumously inducted into the Paris Pantheon as the first black woman. That's a very special honour, isn't it?

Marie Cravageot: As the sixth woman - but the first black woman - to be inducted into the Panthéon on 30 November 2021, Joséphine Baker is an example of a woman full of fighting spirit and conviction.

The tributes dedicated to her emphasise her struggles and her commitment against poverty, racism, injustice, occupiers, but also against violence against women, as she herself was forced into marriage at the age of 13. Several documents bear witness to her struggles and her support for the country that had taken her in.

Without denying her country of origin, she chose France because "France has made me what I am. I will be eternally grateful for that. [...] The moment you find absolute and complete happiness, you can say with conviction: this is my country."

This inclusion in the Panthéon, the temple of recognition by the fatherland - "Aux grands hommes la patrie reconnaissante" (The great men are indebted to the fatherland) - can be seen as a tribute to this commitment.

Josephine Baker herself wrote several autobiographies, each of which tells a different story about her life. How do we remember her today?

Marie Cravageot: Today, Josephine Baker is honoured by her induction into the Panthéon in 2021, her Château des Milandes, which serves as a museum, and a cultural and artistic legacy that lives on through fashion, cinema and music. Thanks to her involvement in the Resistance and her commitment to civil rights, she remains a powerful symbol of the fight against discrimination and anti-fascist activism.

She continues to inspire artists, fashion designers and choreographers, and her film work is regularly celebrated. As a great variety artist and charismatic personality, Josephine Baker fascinated the greatest: from Cocteau and Calder to Picabia, Cendrars, Simenon, Poiret, Colette and Desnos - her admirers are countless. It is still a source of inspiration for many artists today, including dancers, singers, performers and directors such as Vera Mantero, Mark Tompkins, Chantal Loïal, Fatou Sylla, Lisette Malidor, Marie-Claude Pietragalla, Rosemary Phillips and Jérôme Savary.

Today, a new generation is rediscovering the richness of their artistic personality, but also their commitment to justice and minorities. This is the case for several comic writers - Catel Muller and Jean-Louis Bocquet, Pénélope Bagieu or Maran Hrachyan - who were inspired by the sincerity of her struggle. This also applies to the dancer and choreographer Raphaëlle Delaunay, who retraced the origins of her famous animal dances. According to Raphaëlle Delaunay: "Josephine Baker is at the crossroads of all contemporary trends."

Uwe Blass

Marie Cravageot teaches French literature in the school of humanities and cultural studies. She is an expert on contemporary French literature.