The experienced reality of the painter Frida Kahlo

Dr Peter Lodermeyer / Art History

Photo: Private

The experienced reality of the painter Frida Kahlo

The art historian Peter Lodermeyer on Latin America's most famous painter

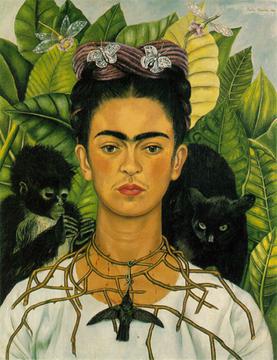

She is considered the most famous painter in Latin America: Frida Kahlo. A traffic accident on 17 September 1925, in which a steel rod pierced her pelvis, was ultimately the trigger for her painterly work. Her art was labelled magical realism very early on. What does that mean?

Peter Lodermeyer: The term 'magical realism' is, like all labels that one tries to attach to such an original and unmistakable oeuvre as Frida Kahlo's, not without its problems. Firstly, this has to do with the fact that it arose in a different context. The art historian and critic Franz Roh first used the term in the mid-1920s to characterise a particular variety of New Objectivity, which differed from Verism, i.e. the very hard, sober realism, in that it integrated dreamlike, unreal or fantastical elements into the depictions. In the 1960s, the term was then increasingly applied to the literature of certain Latin American authors, not least the novels of Gabriel García Márquez. So these are two contexts in which Frida Kahlo's work does not belong. However, if the term 'magical realism' is not understood in a strictly art-historical sense and refers to painting that expresses experienced reality by means of the fantastic and symbolic, possibly also by means of religious or mythological allusions, then it is certainly useful for characterising Frida Kahlo's painting. One need only think of her self-portrayal as a stag wounded by numerous arrows or as a half-nude with an open upper body in which a cracked, crumbling Ionic column appears. These are very impressive pictorial metaphors for the reality of her feelings, the physical impairments, the psychological injuries that characterised this artist's life to such a great extent.

Frida Kahlo with monkeys: self-portrait from 1940, photo: public domain

She said: "People thought I was a surrealist. That's wrong. I never painted dreams. What I depicted was my reality." How did she show this in her paintings?

Peter Lodermeyer: On a theoretical level, Frida Kahlo's justification for not being a Surrealist is not very convincing. Not only because she occasionally actually painted dreams. A painting from 1940, for example, shows her asleep in a bed with a large skeleton covered in fireworks lying on the canopy. The title is 'The Dream'. Above all, however, it does not correctly reflect the basic idea of surrealist art. Surrealism does not mean painting dreams. Max Ernst, one of the most important surrealist artists of all, wrote in his 1934 essay 'What is Surrealism': "So when one says of the surrealists that they are painters of an ever-changing dream reality, this should not mean that they paint their dreams (that would be descriptive, naive naturalism) or that each of them builds his own little world out of dream elements (...)." When he then makes it clear that the surrealists "move freely, boldly and naturally on the physically and psychologically quite real ('surreal'), albeit as yet undefined, border area between the inner and outer world, registering what they see and experience there and intervening where their revolutionary instincts advise them to do so", then I see no reason not to apply this statement one-to-one to Frida Kahlo's painting. Her painting operates precisely in the border area between the real outside world and her inner experience, and she was not lacking in revolutionary instincts anyway: although she was born in 1907, she later changed her year of birth to 1910, not to make herself look younger, but because the Mexican Revolution began in 1910 with the overthrow of the dictatorial President Porfirio Diáz. I don't think we should overemphasise the often quoted and always controversial statement that she was not a surrealist. She uttered it in 1939, no doubt also because she was disappointed by the Surrealists she had met in Paris, but nevertheless took part in the Exposición Internacional del Surrealismo in Mexico City a year later. Just how important this major Surrealist exhibition was to her is shown by the fact that she painted her two largest paintings ever especially for it: the famous double self-portrait 'The Two Fridas' and the painting 'The Wounded Table', which has unfortunately been lost.

Kahlo was even married twice to the world-famous Mexican painter Diego Rivera. Did this amour fou also influence her artistically?

Peter Lodermeyer: Today we would probably say that Diego Rivera was married to the world-famous Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. Even though Rivera has by no means been forgotten as a painter, especially not in Mexico, his wife has long since surpassed him in terms of fame. Indeed, the turbulent relationship with Diego Rivera had an enormous artistic influence on Frida Kahlo. It can be said that this marriage was the second decisive driving force behind her painting, alongside her physical injury. This can only be seen indirectly in many of her paintings, for example when she is shown in a tearful, sad mood, which often had to do with her suffering from Diego's constant infidelities. He even had an affair with her younger sister Cristina. Frida divorced him in 1939, but they remarried in 1940 because they could not live without each other. It is well known that at some point she was no longer too strict about marital fidelity. Just how immensely important Rivera was to the painter is particularly evident in the paintings in which he himself can be seen. There are self-portraits of her in which she wears a likeness of Rivera on her forehead like a third eye, which makes it clear that he dominated her thoughts and feelings. It is also remarkable how the admiration and adoration she felt for her husband increased over time. In the painting 'Diego and Frida 1929-1944', she painted a head composed of the left half of her face and Diego's right half, a clear indication of her feeling of inner togetherness, a fusion fantasy, one could say. The halves of her face complement each other like the light and dark sides of the moon, which can also be seen in the picture. In a diary entry from around 1947, she calls Diego her father, her mother, her son, she writes "Diego = me" and even "Diego universe". Her adoration for him sometimes took on almost religious traits.

At the beginning of the 1940s, the painter noted the meaning of her colours in her diary. Do you have to know the meaning of her colours in order to understand her paintings?

Peter Lodermeyer: No, you don't have to. The sentences that Frida Kahlo wrote about the meaning of colours are anything but a systematically elaborated, consistent colour theory that would form the basis of her paintings. Rather, they are associative and sometimes contradictory statements. For example, she wrote about the colour yellow: "Madness, illness, fear. Part of the sun and joy". To consider whether every yellow flower or fruit in Frida Kahlo's work signalled madness, fear or joy would be very misguided. She associated the colour leaf green ('Hoja Verde') with: "Leaves, sadness, science. The whole of Germany has this colour". Sadness, science, Germany - this triad is at least as open to interpretation as her pictures themselves, which would also lead to the question of what image of Germany the artist had - not forgetting that her father Wilhelm Kahlo was a German, a photographer from Pforzheim. So, the meanings of colour that Kahlo noted in her diary do not provide a master key to understanding her paintings. Nevertheless, it is good to know them, because then you can take a closer look and consider for yourself whether or not the image and text correspond. For example, if you look at the highly symbolic painting 'The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Me, Diego and Mr Xólotl' from 1949, you will notice the different colours of the two halves of the picture. On the left, the dominant colour is brown, the earth, while on the right there is a poisonous, light yellow-green. Here it is revealing to know that the painter had noted: "(Light yellow-green) More madness and mysteries. All ghosts wear clothes of this colour or at least underwear like this." But if you notice motifs such as yellow-green leaves or parrots in some of the self-portraits, you can hardly assume that they are ghosts.

Kahlo was also very political; as a convinced communist, she was initially close to Trotsky, with whom she also had an affair, but then followed Stalin, of whom she even painted two portraits. Above all, her turn to the pre-colonial culture of the Indians and folkloric and mythological Mexican themes can only be understood against the backdrop of the various cultural debates in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution. How is your deep affection for your country's cultural heritage reflected in your pictures?

Peter Lodermeyer: Her attachment to her homeland is evident in numerous pictorial subjects that originate from Mexico's history and popular culture. There are motifs such as statuettes from the pre-Columbian Nayarit culture or the Xóloitzcuintle, the Mexican naked dog, which is associated with the fearsome Xólotl, the Aztec god of lightning, fire and death. The skeletons and skulls, which are particularly well known from the famous Día de los Muertos, and the Judas figure, which is decorated with fireworks and ritually burnt on Holy Saturday, come from popular culture. Some of Frida Kahlo's paintings are modelled on popular votive images that were placed in churches in thanksgiving for the healing of illnesses, for example. Frida Kahlo and her husband had a collection of hundreds of these naïve pictures. However, her commitment to Mexican culture is most striking in her style of dress, the Tehuana costume, which she usually wore after her marriage to Diego Rivera. Tehuana-style dresses, which she also wears in most of her self-portraits, are a reference to the traditional costume of the Zapotec women in the state of Oaxaca. These women had a reputation for being particularly proud, beautiful and brave. If you are very strict, you could accuse the artist of cultural appropriation, and some critics have indeed done so, because Kahlo was by no means a member of the indigenous Zapotec people, the original inhabitants of Mexico, but came from the upscale, westernised Coyoacán, which became a district of Mexico City in 1929. It is interesting to note that the sporting goods company Adidas recently had to withdraw sandals from the market that quoted a traditional motif from Oaxaca. The indigenous people had lodged a protest against this and obtained an apology from the company. Incidentally, Frida Kahlo's political stance is certainly the most problematic aspect of her extremely fascinating artistic career. When she died, there was an unfinished portrait of Stalin on her easel. You have to imagine that: She and her husband were friends with Leon Trotsky, she even had a brief affair with him and gave him one of her self-portraits. Then, on 20 August 1940, Trotsky's skull was smashed in with an ice pick by Ramón Mercader, an agent of the Soviet secret service NKDW, just a few minutes' walk from Kahlo's house, the Casa Azul. The fact that she finally dedicated a homage picture to Stalin, the person who ordered this political murder, is quite disturbing and shows her uncritical attitude towards communist ideology.

The two Fridas, 1939,

Photo: public domain

After her death, her works fell silent, and it was not until the women's movement in the 1970s that she was rediscovered. Today, she is a figure of identification for women all over the world. Why is that?

Peter Lodermeyer: Firstly, a personal observation. In 2024, the main exhibition "Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere" was shown at the Venice Biennale, curated by the Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa. Dozens of paintings, some of them large-format, were on display in one of the exhibition rooms. However, the majority of visitors gathered in front of a tiny picture measuring only around 30 by 25 centimetres: Frida Kahlo's self-portrait 'Diego and I' from 1949. I was there several times, with queues forming in front of it each time. The crowds were so big that a security guard was assigned especially for this picture. The whole thing had the character of a pilgrimage site. It was there that I realised once again that Frida Kahlo has long held the status of an icon. Some time ago, I came across an article online in which she was dubbed a "cult figure, style icon and supergirl". With a personality as complex and contradictory as Frida Kahlo, one can find numerous starting points for identification; she is a projection figure for a wide variety of concerns. The feminists of the 1970s perceived her above all as the victim of her notoriously unfaithful husband, who had contributed significantly to her story of suffering. Later, her bisexuality was emphasised, the fact that she also had love affairs with women. This and the pictures showing her in men's clothing attracted the attention of the queer community. Even physical peculiarities such as her fused eyebrows and upper lip fuzz, which can be seen in many photos and self-portraits, have been celebrated as a sign that she has not adhered to common female beauty norms and has accepted herself as she was - keyword body positivity. As themes such as post-colonialism and non-European art, particularly from the Global South, have attracted a great deal of attention in the art world in recent years, Kahlo's "Mexicanidad", especially her style of dress, which is based on the Tehuana costume, has been particularly emphasised. But she has certainly received the most admiration for making her physical and emotional pain fruitful, for rebelling against her fate with the help of painting and creating something lasting in an art world that was still dominated by men like Diego Rivera at the time - self-empowerment would be the fashionable buzzword for this.

There are 143 paintings by her, many of which can only be shown in Mexico. How would you describe her works today?

Peter Lodermeyer: You can start by thinking about the number 143. Is that a lot or a little? If you think of a painter like Edvard Munch for comparison, who also placed his personal suffering and existential sensitivities at the centre of his work, then there is a difference, because his catalogue raisonné lists around 1,800 paintings, plus a huge body of prints. In contrast, Frida Kahlo's oeuvre seems very small. But when you consider that even a world-famous painter like Johannes Vermeer probably only produced 36 or 37 paintings, and Caravaggio around 70, this is put into perspective. And we must not forget that Frida Kahlo painted under difficult health conditions and only lived to the age of 47. There are undoubtedly differences in quality between the 143 paintings. A number of paintings do not appear to be fully developed, especially in her early years as a painter, and then her strength declined noticeably in the last years of her life. But there are at least two or three dozen paintings that have achieved an almost iconic status and entered the collective visual memory for good reason. These works reveal a very unique, unmistakable style with a high recognition value; they continue to be emotionally moving, and this is certainly because basic human sensitivities such as vulnerability, pain, grief, love, jealousy, but also an irrepressible will to live are impressively addressed here. A few days before her death on 13 July 1954, she completed a still life with watermelons entitled 'Viva la Vida': Long live life!

Uwe Blass

The art historian, author, critic and curator Dr Peter Lodermeyer teaches art history in the school of art and design at the University of Wuppertal.