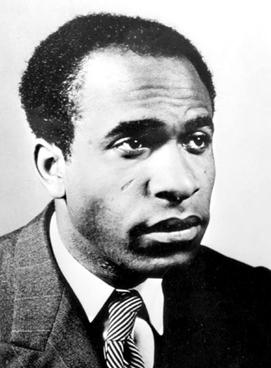

The freedom fighter Frantz Fanon

Marie Cravageot / Romance Studies

Photo: Jan Wengenroth

The militant vision of decolonisation

Marie Cravageot on the freedom fighter Frantz Fanon, born 100 years ago

The psychiatrist Frantz Fanon was a central figure in the African independence movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Who was he?

Marie Cravageot: Frantz Fanon was born on 20 July 1925 in Martinique. He is one of the most influential figures in 20th century anti-colonial thought. His powerful analysis of the dynamics of power, race and colonialism has inspired activists around the world. His ideas influenced political struggles as well as academic fields such as philosophy, psychology and decolonial thought. Fanon embodied a militant vision of decolonisation that combined theory and action. Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) led several lives in one. He was an anti-colonialist psychiatrist, essayist, revolutionary and intellectual with roots in Martinique. He is best known for his analyses of the psychological effects of colonialism on individuals and societies and for his role in the African independence movements.

Fanon studied psychiatry in France and worked in hospitals in Algeria during the war of independence. He is the author of 'Peau noire, masques blancs' (1952), an analysis of the psychology of the black man in a colonial context, and of 'Les damnés de la terre' (1961), a critique of colonialism and a reflection on revolutionary violence. He played an important role in the independence movements and joined the Algerian FLN (Front de Libération Nationale). There he used his skills as a psychiatrist to treat the fighters and analyse the psychological consequences of the war. His work had a profound influence on the decolonisation movements and on contemporary political and social thought. All in all, Frantz Fanon was a committed thinker whose work contributed significantly to the understanding of colonialism and its effects and to the struggle for the emancipation of colonised peoples.

Frantz Fanon

Photo: public domain

As a 17-year-old, he fought against the Vichy regime during the Second World War and experienced racism himself. Fanon realised at the time: "French culture is everything. The rest is nothing. This creates a feeling of inferiority among the population. What did he base this on?

Marie Cravageot: Frantz Fanon volunteered long before the required age to defend Free France against National Socialism. He felt completely French at the time and joined the Free French Forces under the leadership of General de Gaulle in 1943 without reluctance in defence of the "French fatherland". He did not question his identity as a French citizen in any way. "In the Antilles, the young black man who constantly repeats 'our fathers, the Gauls' at school identifies himself with the explorer, the civiliser, the white man ...", Frantz Fanon later wrote in 'Peau noire, masques blancs' (Black Skin, White Masks). He left Martinique in 1944 and, after receiving brief officer training in North Africa, took part in the fighting near the Swiss border. There he was wounded and decorated for his fight.

Fanon learned about the racial hierarchy in the army - the Senegalese riflemen were at the bottom of the scale - and the dark side of colonisation, with starving children in the streets of Algiers. He fought bravely in France and was honoured with the War Cross by General Salan, the man who opposed General De Gaulle at Algerian independence.

Today, Frantz Fanon's name echoes around the world, an unavoidable point of reference when it comes to the situation of black people and the decolonial violence that exploded after the Second World War. It was during this war that he became aware of the colonial violence and racial discrimination that dominated the imperial order. When Frantz Fanon committed himself against National Socialism at the age of 17, he believed he was defending the republican values that had supported the abolition of slavery. As a witness and victim of racism in the army, this led him to question the war and see it as a white man's war. This experience was a turning point in his world view and fuelled his criticism of colonialism.

In 1953, as head physician in a psychiatric hospital in Algeria, he trialled the system of "social therapy". How did he go about it?

Marie Cravageot: In 1953, Frantz Fanon introduced "social therapy" as head physician in the psychiatric hospital of Blida-Joinville in Algeria, which broke with the colonial practices of the time. He did this by introducing major changes to the way the hospital worked. For example, he created a more humane environment by encouraging group discussions, giving more responsibility to the nursing staff and improving the patients' living conditions. He considered the importance of culture to the psychology of his patients and recognised the cultural characteristics of each individual. He introduced activities such as a patient newspaper, a café and a football pitch to encourage social interaction and patient autonomy. He helped with the restoration of the mosque, recognising the importance of spirituality for some patients. He gradually supported the Algerian underground resistance movement.

Fanon tried to transform the psychiatric hospital into a place of life, taking into account the individual and collective needs of his patients while placing himself in the context of the struggle for Algerian independence.

His work there was also incorporated into his writings. Can you give an example?

Marie Cravageot: Frantz Fanon's work has influenced several generations of anti-colonialists, civil rights activists and specialists in post-colonial studies. Since the publication of his books (Peau noire, masques blancs, 1952; L'An V de la révolution algérienne, 1959; Les Damnés de la terre, 1961), it was known that many of his writings, especially his psychiatric writings, would remain unpublished or inaccessible.

This material forms the core of the book 'Ecrits sur l'aliénation et la liberté', which was compiled and presented by Jean Khalfa and Robert JC Young after patient collecting and lengthy research. The reader will find Fanon's published scientific articles, his dissertation in psychiatry as well as some unpublished texts and texts published in the house newspaper of the hospital in Blida-Joinville, where he worked from 1953 to 1956. Also included are two plays written during his medical studies ('L'Œil se noie' and 'Les Mains parallèles'), the correspondence that could be found, as well as some texts published in El Moudjahid after 1958 and not included in 'Pour la révolution africaine' (1964). This remarkable collection is complemented by an exchange of letters between François Maspero and the writer Giovanni Pirelli on a project to publish Fanon's collected works, as well as a thorough analysis of Fanon's work. The publication of these writings on alienation and freedom represents a real publishing event, as they provide a new perspective on Fanon's thought and their relevance in both the psychiatric and political fields remains as relevant as ever. The book brings together academic texts, newspaper articles, theatre plays and correspondence and offers a comprehensive overview of Fanon's thoughts on alienation and freedom, particularly in a colonial context. In the scientific articles and his dissertation in psychiatry, Fanon examines the links between psychology and society, particularly in the context of colonisation. His newspaper articles provide an insight into Fanon's clinical practice and his reflections on psychiatry. The theatre plays bear witness to Fanon's talent as a writer and his reflection on the human condition. This collection contributes to the completion of the edition of Fanon's collected works by bringing together rare and previously unpublished texts. By presenting these diverse writings, the book provides a deeper understanding of Fanon's thought, both in terms of its psychiatric and political aspects.

He makes the dangers of racism and colonialism particularly clear in his book "The Damned of the Earth". The work was widely printed in Germany and abroad in the early years. The sentence "To kill a European is to kill two birds at once ... What remains is a dead man and a free man" could be seen as an instruction manual for the armed liberation struggle that Fanon propagated, although this sentence comes from the preface to the book by Jean-Paul Sartre, doesn't it?

Marie Cravageot: Yes, indeed, the quote "To shoot a European is to drop two flies at once... What remains is a dead man and a free man", actually comes from Jean-Paul Sartre's foreword to Frantz Fanon's 'Damnés de la Terre' (The Damned of the Earth). It is true that this sentence, which is often associated with Fanon, describes the process of decolonisation as a violence inherent in liberation. However, Fanon himself describes violence in his book as a necessity in the struggle against colonialism, but his analysis is more complex and nuanced. In fact, his book 'Les Damnés de la Terre' examines the psychological effects of colonialism on the colonised and explores violence as a possible response to colonial oppression. Published in 1961, this work is an analysis of the colonial system and its effects on the psyche of colonised individuals, often described as a form of dehumanisation. When Fanon wrote this work, he already knew that he was suffering from leukaemia. However, the sympathiser of the Algerian struggle for independence was lucky that the book was published during his lifetime, although it was not allowed to be published in France. With 'The Wretched of the Earth', Fanon wanted to write more than just a political testament. As a trained doctor specialising in psychiatry, he attempts to explain the state of mind of colonised peoples and the means they must use to free themselves from colonisation. Although the term "new man" only appears in a few places in the text, it is considered the centrepiece of the work published by Maspero. It refers to the psychology of the colonised, who have nothing to lose in their situation if they resort to armed struggle. The fact that Fanon's message provoked strong reactions when it was published in 1961 was primarily due to the context in which it appeared, namely the period of decolonisation in Africa. France was in the middle of the Algerian War at the time. The work therefore raised concerns among the French authorities, who saw it as an "attack on the internal security of the state". On the other hand, the preface to the original edition is actually signed by the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. In his remarks, Sartre uses very harsh words and goes further than Fanon by justifying, among other things, attacks on civilians. Although this preface promoted the international recognition of the 'damned of the earth', according to the writer Raphaël Confiant, it also helped to portray Fanon as the antithesis of Mahatma Gandhi or Martin Luther King, two advocates of non-violence. Nevertheless, his book will remain a reference for opponents of colonialism in its various forms. Fanon does not advocate senseless violence, but rather violence that is necessary to break the chains of colonial oppression. He emphasises that this violence is the result of the systemic violence of colonialism itself in order to ensure greater social justice.

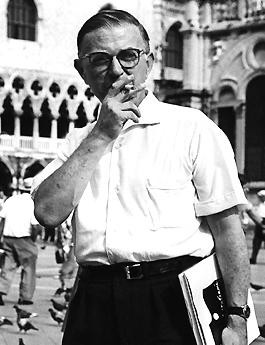

Jean-Paul Sartre in Venice in 1951

Photo: public domain

How did Fanon and Sartre know each other?

Marie Cravageot : The meeting between Jean-Paul Sartre and Frantz Fanon was brief but formative, especially through the preface that Sartre wrote for Fanon's book. At the time, Sartre was an important figure in existentialism and a staunch opponent of colonialism. He was an advocate of the liberation of oppressed peoples. The two met in Rome in the summer of 1961. Fanon, who wanted to meet Sartre, was introduced to him by Simone de Beauvoir. Fanon spent three days in dialogue with Sartre, de Beauvoir and Claude Lanzmann and hoped for a foreword by Sartre, which he received. The two men shared a deep commitment to decolonisation and the fight against oppression. However, their approach was different. While Sartre was aware of the colonial reality, he remained a Western intellectual, while Fanon's experiences and analyses emphasised the psychological mechanisms of colonisation and the importance of struggle for individual and collective liberation. Sartre saw violence as a response to colonial violence, while Fanon saw it as a modality of liberation immanent to the struggle.

Fanon's central theme is the analysis and overcoming of racism and colonialism, but the treatment of these phenomena changes in Fanon's thinking due to his active participation in the Algerian war and his political experiences. Can you explain this?

Marie Cravageot: Indeed, Frantz Fanon's thinking on racism and colonialism evolved significantly as a result of his involvement in the Algerian War. Originally, Fanon analysed these phenomena from a theoretical and psychological perspective, but his direct experience of colonial violence and the fight for independence changed his approach. Before his involvement in the Algerian War, Fanon analysed racism and colonialism in a theoretical way, focusing on their psychological effects on individuals. He examined how colonisation alienates both the colonised and the coloniser. His works, such as 'Peau noire, masques blancs' (Black skin, white masks), analyse the effects of race and colonialism on identity. Fanon's participation in the Algerian war led him to see violence as a necessary response to colonial violence. He argued that the colonised, robbed of their humanity by the coloniser, must use violence to liberate themselves and regain their dignity. Fanon's participation in the Algerian struggle made him aware of the complexity of the decolonisation process. He examined the effects of colonisation on society and the psychology of the individual, but also the internal dynamics of decolonised society. Fanon's experiences led him to emphasise the importance of political action and armed struggle in the fight for independence. In his view, decolonisation must not be limited to a purely formal liberation, but must include a radical transformation of social and political structures. In Algeria, Fanon criticised colonial psychiatry, which contributed to the domination and stigmatisation of Algerians. He proposed an alternative psychiatric approach that paid attention to the cultural and social context and addressed the subjectivity of the person being treated.

With "The Wretched of the Earth", he also posthumously became a central figure in the US Black Power movement of the late 60s and early 70s, didn't he?

Marie Cravageot: Yes, that's exactly right. 'The Wretched of the Earth' by Frantz Fanon was an important point of reference for the Black Power movement in the USA in the late 1960s and early 1970s. His analysis of colonial violence, the psychology of the colonised and the need for a radical liberation struggle resonated with Black Power activists who wanted to fight against systemic racism and oppression in the US. Indeed, Fanon's work, published in 1961, was perceived as a powerful manifesto for decolonisation, not least because of Jean-Paul Sartre's preface, which legitimised violence as a means of liberation. Although this preface was shocking to some, it helped to make Fanon's work internationally known, especially among liberation movements in colonised countries and intellectuals engaged in the anti-colonial struggle. Black Power as a movement sought to emancipate the black American community by taking political and economic power, but also by affirming black identity and challenging the existing social and racial order. In this context, Fanon's ideas, which emphasised violence as a means of liberation and the need to transform the psychology of the colonised, were well received. On the other hand, Fanon's work was criticised by some, particularly for its perceived overly radical approach and its emphasis on violence. Nevertheless, it remains a major work of post-colonial thought and continues to inspire struggles for social justice and liberation around the world. For example, Fanon's 'The Wretched of the Earth' was a central point of reference for the Black Power movement and influenced its view of the struggle against racist oppression and the need for radical liberation action.

The cultural scientist Onur Erdur says: "Thanks to the 'Black Lives Matter' movement, there is more discussion today about how to deal with colonial monuments or the renaming of streets. Fanon reminds us today that the discussions are about politically correct language, about a theatre of power and violence. So, in order to be able to meet each other without being disparaged, we must also change our language." Is that still too difficult for us?

Marie Cravageot: Frantz Fanon's work analyses the influence of language on power relations and cultural identity, particularly in the context of colonialism. He analyses how language is used as a tool of oppression and as a means of maintaining colonial dominance. At the same time, he views language as a means of emancipation and the construction of a new, post-colonial identity. Fanon argues that the language of the colonial rulers is not only a means of communication, but also a means of constructing superiority and oppressing the colonised population. By mastering the coloniser's language, the colonised person is forced to identify with a foreign identity, which can lead to a loss of identity and alienation from their own culture. The language of the coloniser is elevated to the norm, while the language of the colonised population is devalued, which cements the existing power relations. Fanon emphasises the need to question the language of the coloniser and to use one's own language as a means of asserting oneself and reconstructing one's own identity. Language can serve as a tool for organising resistance, articulating political demands and shaping a new, post-colonial society. Fanon sees the development of a new language that reflects the experiences and perspectives of the former colonised as a way of freeing oneself from the constraints of colonialism and developing a new, self-determined identity. Fanon thus views language as a central component of the colonial dynamic. He analyses how language serves as a tool of oppression and a means of constructing identity, while at the same time emphasising its potential for emancipation and the creation of a new, post-colonial world.

Frantz Fanon's work continues to influence contemporary debates on domination, language and liberation, particularly in a post-colonial context. His analyses of violence, the psychology of the colonised and language as an instrument of power continue to have an impact today and encourage critical reflection on structures of domination and strategies of resistance. The consequences of this linguistic dominance can still be seen today in post-colonial societies, in which the structures and mentalities inherited from colonialism persist. This can be seen in various areas such as education, work and the media. Fanon's considerations can still be discussed today.

Uwe Blass

Marie Cravageot teaches French literature in the school of humanities and cultural studies. She is an expert on contemporary French literature.