100th anniversary of the death of the composer Erik Satie

Christoph Spengler / Director of the choir and orchestra of the University of Wuppertal

Photo: Sergej Lepke

"I came very young into a very old world"

Christoph Spengler, director of the Bergische Universität choir and orchestra, on the 100th anniversary of the death of composer Erik Satie

Erik Satie died on 1 July 1925 in Paris. His works are often characterised by an over-emphasised simplicity and clarity. What does that mean?

Christoph Spengler: The question implies understanding the "new simplicity" of Satie's music as a weakness. I see it more as an artistic statement. In my view, the music of the late Romantic period was at an impasse with its opulence, ever-increasing instrumentation (think of Gustav Mahler's "Symphony of a Thousand") and expansive work lengths. How should things continue - even larger, even more expansive, even more emotional works? It's hard to imagine, and that was probably the motivation for Satie to radically reduce his music - simple harmonies, clear melodies, little emotional development, a rather playful style - always with a wink.

Satie often composes in such a way that you think the piece is about to continue or develop - but then it stops. Or returns to the beginning. In a way, he anticipated much of what minimal music of the 20th century would later turn into a principle.

At the age of 13, his stepmother enrolled him at the Paris Conservatoire, but he left two years later due to a "lack of motivation". He only resumed his music studies at the age of 40. But he had already composed various pieces of music by then, hadn't he?

Christoph Spengler: That's right. And they weren't just any juvenile works, but compositions that are among his most famous and are still associated with his name today. Satie was in his early 20s when he wrote the three Gymnopédies, and the popular Gnossiennes also date from this early creative phase.

I do not believe that his early studies had much influence on these first works and see him more as a kind of self-taught composer who devoted himself primarily to the instrument he learnt to play as a child - the piano. His work as a pianist in cafés in Montmartre will certainly have had an influence on the sound world of these works.

He was not exactly considered over-motivated during his late, second study programme - he was already 40 by then. It is even said that he simply wanted to have an education in order to be taken more seriously as a composer, especially by the art world, as he was criticised for his constant tendency to combine popular and so-called "serious" music - not least by his friend Claude Debussy.

Among his best-known works are the three Gymnopédies, piano pieces composed around 1888. What makes them so special?

Christoph Spengler: The Gymnopédies are three short piano pieces, very slow, almost floating, without a trace of virtuoso brilliance. It is almost static music that does not seek any development in the classical sense. The sound of the three pieces seems to float above the keys, carried by simple yet surprisingly colourful harmonies. This music, which is "simply there", leaves room for thoughts, for atmosphere, and deliberately does not constrict the listener. It creates a feeling of timelessness, a "non-sad melancholy" - and yet is still very expressive. I think these pieces are unique, beyond classical pigeonholes, and that is precisely what makes them so fascinating.

They are a wonderful example of Satie's (later) idea of "background music" or, as he called it, "musique d'ameublement" - which translates as "furniture music". Music, he thought, should simply be in the room, like a piece of furniture, thus setting himself apart from the classical concert concept of music that one should "listen to". In the cultural understanding of the time, this was a radical idea - to write music that should be "overheard" and rather create an atmosphere in the background. For example, he wrote musical fragments to accompany an art exhibition with the aim that they would hardly be noticed - which, however, was not the case.

With this attitude, Satie anticipated much of what we take for granted today. We spend a considerable part of our everyday lives surrounded by music that we barely notice, precisely because it is "just there". There isn't a shop without music blaring through the loudspeakers, hardly a car radio that doesn't accompany the conversations of travellers.

What should not be underestimated is that music creates an immensely strong atmosphere, even if it is not consciously perceived. A good example of this is film music, which essentially reinforces the emotionality of the images, the atmosphere of the locations and the drama of a film. This becomes particularly clear when you watch scenes from films without music.

Erik Satie (1919)

Photo: public domain

He was a quirky loner, a minimalist between all the stools and described himself as a phonometrographer who made a living as a pianist in the Chat noir and other cabarets of Montmartre in the 1890s and said of himself: "I came very young into a very old world." What did he mean by that?

Christoph Spengler: This sentence says a lot about Satie's self-image - and perhaps also about his pain. I think he saw himself as someone who was ahead of his time, but at the same time felt alienated from the world he was born into. The musical and social conventions of the late 19th century were alien to him: too bourgeois, too serious, too self-satisfied. Satie, on the other hand, was playful, ironic, radical - and did not want to belong.

His self-designation as a phonometrographer, i.e. a "sound meter", is typical of this outsider spirit. Instead of stylising himself as a composer of great genius, like many of his contemporaries, he chose a technically sober term - almost a caricature of what it meant to be an artist at the time. This is even reflected in his style of dress: he wore the same corduroy suit every day, of which he had bought seven.

His work as a café pianist certainly characterised his compositional style and also ensured that he was so "grounded" and thus took a completely different path to, for example, the composers of the New Viennese School such as Schönberg, Berg and Webern, who pursued completely different musical ideals with highly complex sound structures.

Some of his piano works bear titles such as "Vertrocknete Embryonen" (Embryons desséchés) or "Wahrhaft schlaffe Präludien für einen Hund" (Véritables Préludes flasques pour un chien). It is said that he was the forerunner of Dadaism. In any case, he also worked with typewriters, foghorns and electric bells, didn't he?

Christoph Spengler: Yes - and with full intent. Satie had a pronounced sense of the absurd, the ironic and the playful. The titles of his works often seem like small provocations against the seriousness and gravity of so-called high culture. "Truly Slack Preludes for a Dog" is not just a comical title, it is a musical commentary on the stiff etiquette of musical tradition.

His reference to Dadaism is not far-fetched. Like the Dadaists, he loved to play with sense and nonsense, with expectation and disappointment, with language and the loss of meaning. You could say that Satie was Dada before Dada existed.

The fact that he also experimented with sound - with typewriters, foghorns or electric bells - shows his courage to transgress boundaries. Such instruments appear, for example, in the theatre piece Parade, which he created together with Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso. That was in 1917 - in the middle of the First World War. Incidentally, working on it was anything but easy for him because he found it difficult to work with others.

Satie opened a door in a playful way - to a musical world in which everything was allowed. And that was quite radical at the time.

Great pianists would avoid Satie's piano works at all costs. Why is that?

Christoph Spengler: There are several reasons for this. Firstly, the most seemingly banal one is that his works are usually not particularly difficult to play technically and the interpreter is therefore deprived of the opportunity to demonstrate his virtuosity. At the same time, and this is where it gets interesting, the pieces are mercilessly transparent in their strong reduction and simplicity, every touch counts, everything is totally open, far from being "enveloped" by a large, accompanying orchestra or clouds of sound pedal utilisation. When Satie's music is played "really well", it sounds very simple, and perhaps this is precisely the worry that the audience only perceives this without understanding that the art lies precisely in making it sound exactly like this. That is an uncomfortable demand that not many people want to face.

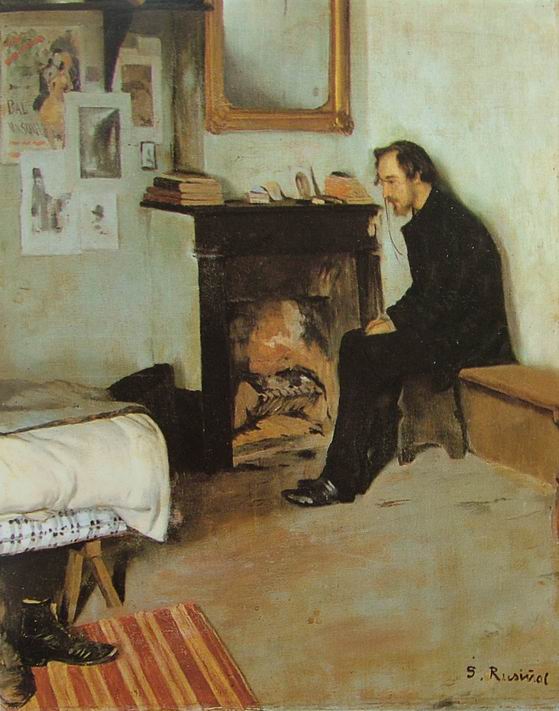

Santiago Rusiñol: Erik Satie in his room (1891),

Fozo: public domain

Satie knew and worked with the artistic avant-garde of his time, i.e. with artists such as Claude Debussy, Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau and Maurice Ravel. Experts say that he was one of the most underrated composers of the 20th century. Would you agree with that?

Christoph Spengler: Well, Satie fell out with the great Claude Debussy, with whom he had a close friendship, at the end of his life because he didn't appreciate Satie's tendency to incorporate elements of popular music into his compositions. It is striking that we encounter very little of Satie's music in everyday concert life, and when we do, it is almost always only the early works as described above. He was always an unwieldy contemporary on the scene with his refusal to concern himself too much with counterpoint and harmony. At the same time, he paved the way for musical developments that had an impact far beyond his lifetime - minimal music, film music, the concept of "ambient music". Satie questioned the reception of music itself, he challenges us to listen in a different way or even to "listen away".

Satie himself always refused to be heroically honoured - no drama, no tragedy, no grand gesture. He favoured a quirky, humorous, but also poetic view of what music can be. In my view, this made him a very modern composer in his time, and I think, yes, it is fair to say that his importance for much of what we take for granted today is underestimated.

Uwe Blass

Christoph Spengler studied church music in Düsseldorf. He took over the direction of the university choir in 2007 and the orchestra in 2011. In 2016, the rectorate awarded him the University of Wuppertal's Medal of Honour. In 2017, he was appointed church music director by the Protestant Church in the Rhineland.