The largest planetarium in the world was in Barmen

Sabrina Engert / History of science and technology

Photo: UniService Transfer

The largest planetarium in the world was in Barmen

Wuppertal student Sabrina Engert researched Barmen's once largest planetarium in the world in the city archives for her bachelor's thesis

"Barmen once had the largest planetarium in the world, albeit only for five days," says Sabrina Engert, who is studying history at the University of Wuppertal. Fascinated by the history of the Barmen planetarium, about which there is hardly any literature to be found, the student decided to dedicate her bachelor's thesis to this topic. She found interesting documents in the Wuppertal city archives.

City council decides quickly

The construction of the Barmen Planetarium was on the agenda of the city council meeting in Barmen Town Hall on 18 October 1924 and was decided on just three days later. 'The Finance Committee is in principle in favour of the construction of the planetarium in the grounds of the Beautification Association opposite the junction of Augustastrasse and Ottostrasse as proposed by the administration. The project should be developed in such a way that there is the possibility of the building being used for other purposes at a later date. Provision is to be made for the installation of clothes racks. The authorisation of the necessary funds is approved', reports an excerpt from the minutes of the meeting, which Engert found in the city archives. The student explains that this was ultimately not the location where the planetarium was built, as even then, local residents protested against the city's planned endeavour, so that a different, nearby location was chosen. "The planetarium was built within a year above the Barmer facilities on Untere Lichtenplatzerstrasse. It stood opposite the old Barmer Stadthalle and next to the track of the old mountain railway, which you can still see today," says Engert. Anyone familiar with the Barmer Anlagen site can imagine how the magnificent building once stood there.

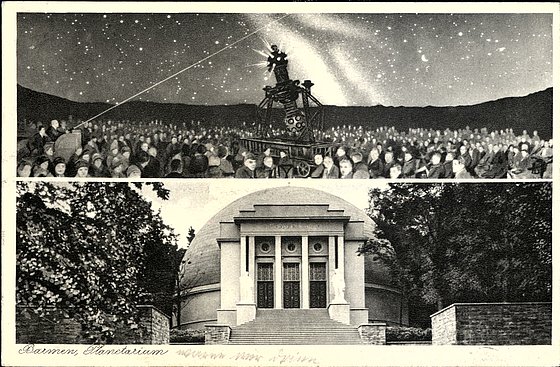

Postcard: Barmen Planetarium

Picture: Engert

The Barmer Planetarium - its heyday from 1926 to 1931

"The planetarium was built after the First World War during the Weimar Republic. During this time - and especially in the first five years - the development of the planetarium is particularly exciting due to the historical circumstances," explains Engert. "In the thesis, I am of course writing the story to the end, so to speak, but between 1943 and 1955, the planetarium unfortunately fell into disrepair and was demolished."

Although the first optical planetarium had already been built in Munich, the first large planetarium was built in Barmen. "The dome in Munich is much smaller, has a diameter of around 15 metres and was not an independent building, but was integrated into the museum building," reports Engert. The projection apparatus was still Model I. The Barmen Planetarium, on the other hand, was a free-standing building, had a dome with a diameter of around 25 metres and was already projection model II. "That's why you can rightly call it the world's first large planetarium in Barmen."

Visitors were amazed by the exterior view alone. Engert explains: "First of all, the dome was reached via twelve-metre-wide stairs, which were decorated on the left and right with statues of Mars and Venus, the deities from mythology, as a link to the starry world. The dome itself was 15 metres high. In front of the dome there was an 11 metre x 4 metre vestibule where the ticket offices were located. The planetarium itself could seat around 600 people. For comparison: in Bochum today there are about 250 seats. The cost of this building at the time was 350,000 Reichsmarks."

The planetarium boom gripped many German cities until 1931. "By 1931, planetariums had opened in Berlin, Dresden, Hamburg, Hanover, Jena, Leipzig, Mannheim, Munich, Nuremberg and Stuttgart," says Engert. There were regular performances and lectures were held, but the economic crisis and the influence of the National Socialists brought the success story to a premature halt.

Postcard: Barmen Planetarium

Picture: Engert

Operations largely ceased in 1931

From 1931, the Planetarium's regular programme was discontinued. Although schools continued to use the programme and individual special events for the public, such as a Christmas show entitled 'Star over Bethlehem', were also offered, the decline had already begun. "In the end, it is not possible to say exactly what reasons contributed to the planetarium's decline and to what extent," explains Engert. However, she has developed three hypotheses through her intensive study of the sources in the city archives. Firstly, it could have to do with the global economic crisis and the mass unemployment that began in 1929, because "this meant that fewer people could afford admission or tickets to the planetarium. That alone could make a visit impossible. In addition, the entire republic was subject to austerity measures and the city of Wuppertal, which was founded in 1929, was also subject to them. As a result, the planetarium received fewer advertising materials, lecture budgets etc. and this in turn naturally led to fewer visitors. Fewer lectures then meant less income - a vicious circle."

A second trigger could also be related to the boom, because just five days after the Barmer opening, another planetarium was inaugurated in Düsseldorf, whose dome was even 4 metres larger in diameter. "Of course, having two optical planetariums doesn't seem so bad at first, but the problem was probably the proximity. The short distance between Wuppertal and Düsseldorf meant that Wuppertal not only lost its exclusivity, but also a large part of its catchment area. People from Erkrath or Solingen, for example, could then choose between Wuppertal and Düsseldorf, which suddenly had the larger planetarium." From 1931, the planetarium fell into a deep sleep. "This term was coined by the daughter of the planetarium's director to describe the state of the building for the next few years," says Engert. The student sees another reason for this in the National Socialists' seizure of power. She also found information on this in the city archives. "There are documents that prove that the Nazis wanted the director, Dr Erich Hoffmann, to give ideologically aligned lectures in the planetarium. I found letters about this in the city archives," reports Engert. "In them, he is asked for suggestions on how lectures in the planetarium could be ideologically adapted. For example, lectures on Germanic astronomy or the Wehrmacht. Hoffmann was unable to fulfil this request satisfactorily. It can therefore be assumed that the National Socialists did not support this educational centre as it did not fit into their ideological framework." Although Hoffmann still endeavoured to have lectures from the Planeatrium included in the N.S. cultural community's lecture series, he was unsuccessful.

Demolition in 1955

On 30 May 1943, around 80% of the built-up area in Barmen was destroyed in an air raid. More than 3700 people were killed. The damage to the planetarium was comparatively minor. "The impact of a bomb that exploded near the planetarium caused a crack about one metre long in the dome. It wasn't actually a huge amount of damage," says Engert, "but parts of the valley were completely destroyed and there were an incredible number of dead and injured. The priority was simply not on the planetarium." And then the magnificent building suffered the same fate as many other buildings. "Over time, moisture got through the dome and made the building unstable. Burglars stole the interior fittings and parts of the technology. I think it would have been very expensive to repair and renovate and many people still remembered that the planetarium was no longer well attended back in the 1930s. In the end, it was decided to demolish the building rather than restore it."

Wuppertal city archive - an important source for the city's history

Sabrina Engert spent many hours in the Wuppertal city archives. She found extensive material there. "It was quite a search," she says with a laugh, "I used a variety of sources, including administrative files from the city of Barmen / Wuppertal. I analysed all the budgets between 1924 and 1939 and included minutes and invitations to meetings." Newspaper articles, but also police reports and private letters rounded off her research. She is particularly grateful for the wonderful support of the staff at the Wuppertal City Archive. "The Sundermann family, descendants of the first director and custodians of Dr Erich Hoffmann's estate, provided me with many sources that gave me exciting insights. For example, there is a hand-written map of the planetarium and a script of a lecture that was given there."

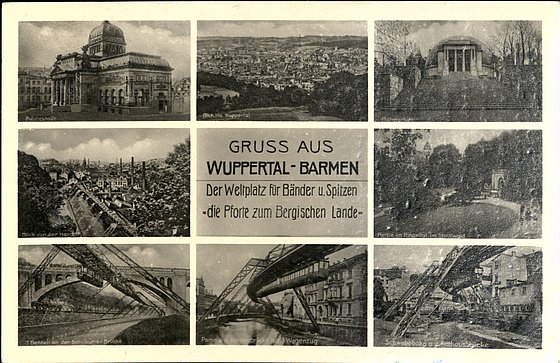

Engert was even able to find and buy original postcards with an image of the Planeatrium and the stamp with Paul von Hindenburg's likeness on the back on the Internet.

Postcard: Greeting from Wuppertal - Barmen

Picture: Engert

Not yet completely forgotten

If you ask young people in Wuppertal about the former planetarium, you will only get quizzical looks, because apart from a memorial stone erected by the daughter of the first director in the Barmen grounds, there is nothing left to remind you of what was once the largest planetarium in the world. Even in reports on the history of the Zeiss planetariums, Barmen is not mentioned. "I think the world's first large planetarium should have a place there, after all Wuppertal and Barmen have a lot to offer in terms of cultural assets. That just shouldn't be forgotten. That's why the topic was so interesting for me, because I could hardly believe that so little is known about the Barmen Planetarium," concludes Engert. "Over 50 per cent of my work is based on sources. I wanted to collect the history, taking into account all available sources and literature. Previously, the few articles have always highlighted individual aspects, but an overall presentation of the history has been lacking until now. I hope that the planetarium will receive more attention in the future and that perhaps others will continue to deal with the topic. Perhaps my bachelor's thesis can serve as a kind of foundation."

Uwe Blass

Sabrina Engert is a research assistant in the History of Science and Technology at the School of Humanities and Cultural Studies at the University of Wuppertal.