Insulation mania in the building trade

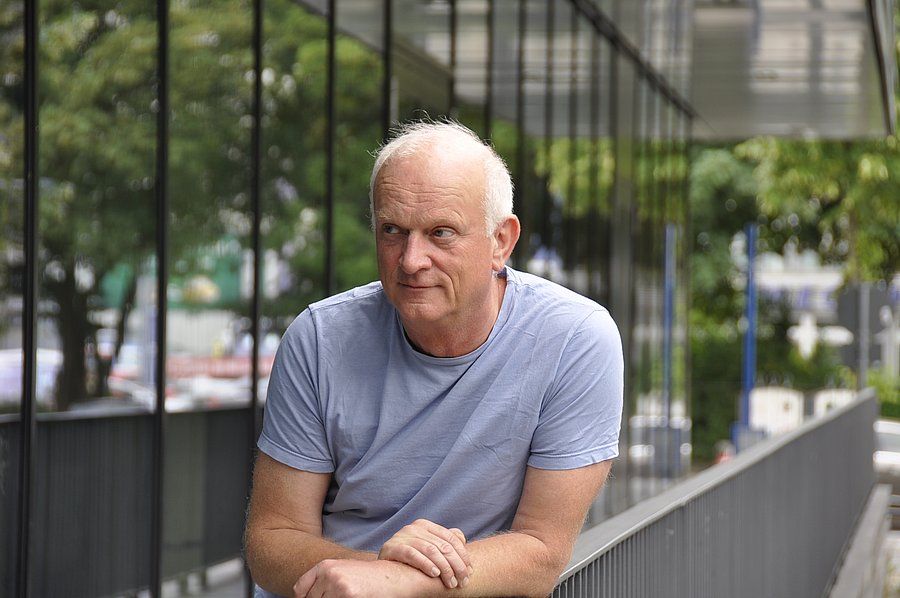

Prof. Dr.-Ing. Christoph Grafe / History and theory of architecture

Photo: UniService Transfer

“We have to allow different temperatures in rooms”

Prof Dr Christoph Grafe on the insulation craze in the construction industry

In the building sector in Germany currently 40 per cent of energy is consumed, two thirds of it by private households alone. If the German government does not want to miss its climate targets, this is clearly too much. Building renovations are supposed to improve the situation. However, is sealing the exterior walls and completely sealing the floors so that air can no longer circulate through them the right approach in the long term? Architect Prof Christoph Grafe takes a critical view and asks, ”Do we really need the same temperature in all rooms?”

The same temperature in all German interiors?

The so-called upgrading of buildings, i.e. insulation, is booming in Germany. Cosy temperatures in all rooms seem to be the order of the day, although some aspects of this do not necessarily apply to the whole country or all people. "I would question," Grafe says, "whether the whole of Germany can be treated equally when it comes to the issue of structural adaptations. If you look at the weather map, it shows significantly different temperatures for Wuppertal, Freiburg, Cologne, or Bremen in winter and summer than in the east of the Federal Republic. In some regions, there are hardly any frosty nights, in others it can get quite cold. The traditional building methods in the regions have always been tailored to these differences: in the north-west, it is windy, but rarely cold. Then a good raincoat is needed rather than a thick woollen coat. This can also be seen in the way buildings were constructed there. "You also have to consider people's different feelings of cold and warmth. Not every room therefore needs to be insulated to the same extent. "I would argue that we should allow different temperatures indoors, if only because we don't do the same thing in every room. We should therefore also pay attention to our different activities. Even the function of body heat or wearing warm clothing is part of strategies of adaptation that have been forgotten. The houses that are being built today, in which building services account for more than half of the construction costs, are over-engineered. Is that really necessary everywhere?"

Problem child of post-war construction

In total, the building stock in Germany amounts to around 21 million buildings, which differ in terms of utilisation, heating requirements, energy consumption, etc. A considerable proportion of them are post-war buildings.

A significant proportion of them, especially in North Rhine-Westphalia, consist of post-war architecture constructed between 1950 and 1975. "These buildings do indeed have deficits. At that time, new industrial materials were often used to build them. They have relatively thinner walls than older houses and have many cold bridges. It will require careful planning and will certainly cost a lot of money to insulate these buildings. All of these aspects bring new problems when you think of the millions of detached houses built from 1965 onwards that need to be made permanently habitable," explains the expert. Grafe sees major problems in the application of the materials often used today for insulation, as their long-term behaviour is still largely unknown. "Do we really know whether these materials, which are used to seal houses in this way, won't lead to new health problems? People have known for centuries what it's like to live in a house made of stone, clay, or wood. Can we say the same for the materials that are now being used? Most of the pollutants we breathe in are actually found indoors. Does the insulation of houses on a massive scale mean that we create the building ruins of the future? " Another aspect of these building measures that has not even been investigated is the impact on other creatures, such as insects, mice, and swallows, which have always lived with people in and around their homes.

In 1922, the Norwegian architect Andreas Fredrik Bugge, professor of building construction, demonstrated the effectiveness of thermal insulation in buildings for the first time in a scientific field experiment. Photo: (CC BY-SA 4.0):

Intelligent designs for traditional construction methods

Added to this is the fact that houses today need to be cooled rather than heated, as the temperature has changed because of climate change.

In German buildings, air conditioning systems are installed in great numbers, while the Arab world shows us that houses can withstand extreme heat even without air conditioning using traditional construction methods. Grafe immediately remembers a collaboration with students who worked on this very topic during the Solar Decathlon Europe 2022[RK1] . "The year before last, we worked with students on the topic of climate change, not technologically but spatially, i.e. architecturally, for all possible climate zones. We all realised that there is a great deal of traditional knowledge about how to influence the indoor climate in a positive way. In the subtropical and Mediterranean climate zones, this includes generating draughts via wind towers, especially in the Middle East, and you can generate much more via the rooms than via technology." It will therefore be the future task of female architects to reactivate this knowledge and apply it here in a temperate climate. Especially with the many small flats that are currently being built, Grafe advises that thought should be given to proper ventilation at the planning stage. "Maybe we won't need chimneys in the future, but wind towers."

The stone as a role model

In Munich, there is a good example of a particularly sustainable office building where employees manage to work without heating and air conditioning. A year-round room temperature of 22 to 26 degrees Celsius can be achieved simply by using the Unipor Coriso brick. "The most important thing about the brick is the fact that, unlike other insulating materials, it is a brick that helps to insulate. This means we have a material that we can already say today how it will behave in the next 30 years because we can compare it with historical stone constructions." Today, principles from the past are being reintroduced in industrial construction in the form of thick walls and heat accumulation. "The stone gives off heat in summer and stores it in winter," Grafe explains. "At the same time, this is a good example of research into building materials, which can now also offer alternatives and thus also return to millennia-old traditions that do without plastic."

Innovative technologies for remodelling instead of new construction on green fields

Everyone always thinks that sustainably built houses are much more expensive. However, an architectural firm in Melbourne (Australia) is proving the opposite with an affordable, ecologically built house. The builders promise that only three bags of rubbish will end up in landfill during the entire construction of the house and work with hardwood panels, polished fine concrete and a butterfly roof that makes optimum use of the sun's rays through solar panels. With additional rainwater storage, double-glazing and LED lighting, residents pay around 2 euros a year for electricity and heating energy providing that they have a normal energy consumption. "Yes," Grafe says, "but Australia is not Europe, which means we have to have a different calculation because we don't actually have any free areas for new buildings here. If the many flood disasters of recent years have taught us one thing, it is this: we must stop the progressive sealing in Europe. In short: even if Chancellor Scholz seems to disagree, we need to stop building on green fields. Therefore, the question arises: how do we deal with what is already there?" Grafe expressly supports the moratorium on demolition formulated by Architects for Future, a group of young female architects together with various chambers of architects and the Association of German Architects (BDA).This means that we no longer tear down old buildings in order to build new ones, but include further construction of the building stock. "In Europe, the very interesting question will be how to use innovative, newly developed technologies for remodelling. We have enormous developments in wood-based construction forms that can be used successfully in remodelling. The generation of renewable energy will also play a role and create new forms, which can be seen in the expressive roof of the house in Australia already. However, we must also make clear to society, clients, and residents that all these development require intelligent design, which must also be valued and paid for. Intelligent design always means higher quality."

Unused straw could be used as building material. Here a bale of straw tied with 4 yarns / Photo: "Alpaca de paja" by Midir / Own work / Licensed under public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The question of materials in the 21st century

In the course of sustainability, materials are also becoming increasingly important. Renewable raw materials such as hemp, which also promises a high level of sound insulation, could be one of the building materials of the future. "Renewable materials are clearly favoured, as are all materials that can be easily separated again, such as tried and tested stone," explains Grafe. "Up until the 18th century, stone was basically taken apart and reused again and again in houses and only replaced by the introduction of glass, steel, and concrete during the Industrial Revolution." Thanks to the sustainability debate and intelligent recycling methods, the material of the 21st century is now the existing material again. "We are reactivating long-existing knowledge."

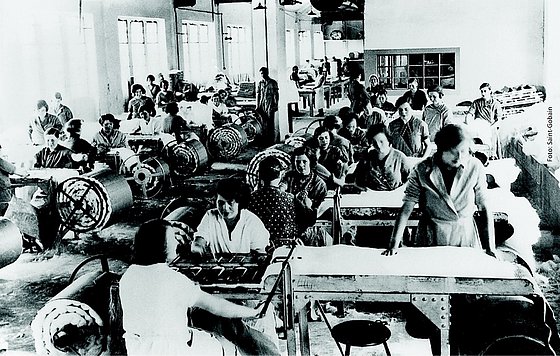

Mineral wool has been around since the 1930s. Photo: Saint-Gobain (public domain):

Building in existing buildings

Grafe concludes by returning to the challenge of converting post-war buildings. The conversion of existing buildings, which were originally built with little sustainability in mind, is also being driven forward in NRW through constructing in existing buildings. "This is a major challenge and is a major concern for us here because the percentage of this building stock in NRW is extremely high," says Grafe. The façades of these buildings in particular are not up to standard and urgently need to be upgraded. For that reason, he is working very intensively with students on how best to treat this architecture. The decision on what to do must always be made on a case-by-case basis. "The structural adaptation of buildings is a necessity that is beyond question. However, it must not be reduced to its technical aspects. We also need to think about new ways of living together so that the modern use of these buildings is not just a stopgap solution."

Grafe knows of a very commendable example of a sustainable building project in Wuppertal, the BOB Campus, located on Nordbahnstraße in the centre of Oberbarmen. Commenting on this new location on the site of a former textile factory, with a day-care centre, classrooms, commercial and communal areas, flats, and a neighbourhood park, Grafe concludes: "I see this as a flagship project in which you can implement this combination of continued construction and new construction. It allows you to see the big picture. It is a sign of renewal in Wuppertal and it is very precisely tailored to the individual parts of the building. It is therefore also an economy of means, because you use exactly what you really need. It is customised and is also an example of finding the intelligence in the existing architecture."

Uwe Blass

Prof Dr Christoph Grafe has held the Chair of Architectural History and Theory at the University of Wuppertal since 2013.