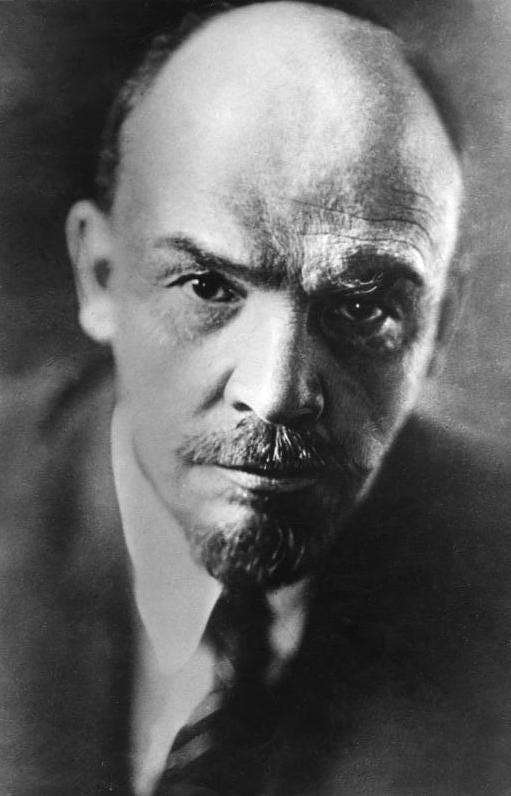

Founding hero or dictator - Vladimir Ilyich Lenin died 100 years ago

Dr. Georg Eckert / History

Photo: Mathias Kehren

Founding hero or dictator -

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin died 100 years ago

An interview with the historian Dr. Georg Eckert

On 21 January 1924, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, better known as Lenin, died in Gorky near Moscow at the age of 54 after an eventful life. How did he get into politics?

Eckert : Lenin came to world-historical political prominence in a sealed railway carriage, which took him from Switzerland via Germany and Scandinavia to St Petersburg in April 1917: after the February Revolution, which brought an end to the rule of the Tsars. Younger revolutionaries in particular had been working towards this for a long time, including in the Ulyanov family. While Lenin was studying for his brilliant school leaving certificate in 1887, his older brother was executed - for his involvement in plans to assassinate Tsar Alexander III. It was by no means only in Lenin's circle that tsarism was seen as an autocracy that needed to be at least reformed, but ideally ended, in order to finally overcome Russia's backwardness. Lenin was therefore already politicised in his youth.

He went underground at the age of 17. Why?

Eckert : First of all, underground is a big word. The Lenin we know is above all a myth - purposefully narrated with a view to the later successful revolution. The young Lenin was not as discriminated against and persecuted as communist propaganda later portrayed him for heroisation purposes. Nevertheless, the execution of his brother, with which the tsarist judiciary wanted to make an example, did not deter him at all; if anything, it strengthened his conviction that it was a despotism. In fact, Lenin became radicalised when he began studying law in Kazan, inspired by radical figures and radical texts, particularly those by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Lenin appropriated them partly by adapting Georgi Plekhanov, who integrated the Russian tradition of the social revolutionary Narodniki, and partly through his own translations, as his executed brother had done. These were texts that advocated an open uprising, the glorified "dictatorship of the proletariat".

He often spent time in exile in Switzerland and Germany. What did he do there?

Eckert : Lenin repeatedly came into conflict with the Russian state power, even if he himself and the later communist propaganda successfully made people forget that, despite all the differences, he was able to pass an excellent university examination. His family certainly belonged to an elite of the tsarist empire, which, however, tended to work towards reforms - unlike Lenin, who now sought and found a platform for his revolutionary agitation. Many Russian exiles were particularly active in Switzerland and Germany. A bohemian community enjoyed radical people and positions there, for example in Zurich, which became a centre for revolutionary agitators, as well as in the Munich district of Schwabing.

In 1902, he published the programmatic pamphlet 'What to do' in Munich under the pseudonym 'N. Lenin', which made him very well known in revolutionary circles. What was his intention?

Eckert : Lenin's aim was certainly to become something of an opinion leader and to distinguish himself as a particularly zealous revolutionary: This was also signalled by the choice of his fighting name "Lenin", which could be understood to mean that its bearer came "from Lena", i.e. had been exiled to Siberia. In any case, he called for a conspiratorial avant-garde of professional revolutionaries who were to organise themselves in secret into a powerful cadre party, distinguished from previous movements by strict discipline and energy. Lenin cultivated a particular rigour not only in theory, but also in practice. In 1903, he successfully managed to split the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party at a party conference held in London: as the leader of the radical "Bolsheviks" ("majorityists"), who would have prevailed against the hesitant "Mensheviks" ("minorities").

As early as 4 June 1917, Lenin announced the Bolsheviks' ambition to take power in the country at the 1st All-Russian Soviet Congress. His demands for the distribution of land to the peasants without compensation and for the expropriation of the richest class of the population quickly became popular. But he had only ever dealt with the problems of the peasants in theory, hadn't he?

Eckert: On the one hand, Lenin was a "theoretician" in his view of the problems of both rural and urban workers. But he was aware of the interpretative power of his theories; the "dictatorship of the proletariat" sounded promising to many. On the other hand, he was a "practitioner" who thought very carefully about how to achieve great impact and also knew how to quickly adapt his teachings - for example, the founding of "Pravda" ("Truth"), which was soon to become the central organ of the CPSU, was based on his initiative. He emphasised his ambitions with radical demands, particularly for the expropriation of the wealthy without compensation. Lenin's slogans resonated even more when Russia's defeat in the First World War was sealed after the failed Kerensky offensive in July 1917. Now many illusions of a moderate bourgeois reform policy were finally shattered, Lenin's appeals, like the "April Theses", tapped into a widespread longing for peace and had an extremely attractive effect on many.

Lenin/Federal

archiv_183-71043-0003,

Vladimir_Ilyich_Lenin

He returned to the empire in 1917 after the fall of the tsar. Under his leadership, the Bolsheviks came to power in the October Revolution. How did that happen back then?

Eckert : With the aforementioned proclamation, Lenin had already demonstrated that he was not open to compromise: neither in matters of fact nor in matters of power. Over the course of 1917, his party systematically destabilised the bourgeois Provisional Government, which had exercised the so-called "dual power" after the February Revolution, together with the Petrograd "Soviet", a representation of workers and soldiers, whose war-weariness the Bolsheviks knew how to exploit. Their July coup still failed, but Lenin was now working underground towards an armed uprising. In November 1917, his Bolsheviks felt strong enough for a violent revolution: the fact that it was called the "October Revolution" is due to the fact that, significantly, the Julian calendar still applied in Russia. Where Lenin's troops were not in the majority, they knew how to secure one by force. Their uncompromising attitude, entirely in the spirit of the cadre party, as Lenin had demanded, was consolidated in the civil war that now broke out. They did not shy away from the use of brute force, and even more, they defined themselves by it. Lenin's particular appetite for risk was a key factor in their success; he harboured no scruples or doubts.

In the years that followed, he called for the "Red Terror" and declared that the use of violence arose from the task of suppressing the exploiters, i.e. "landowners" and "capitalists". The execution of the Tsar's family from 16 to 17 July 1918 was also ordered by him. Had he already lost the ground under his feet by then?

Eckert: Lenin relied on the radical momentum of a revolutionary movement, which could only unfold its full force when it pulled the rug out from under the old system. The murder of the tsarist family, who had long since abdicated, was intended to prevent its members from becoming the unifying shining lights of the "Whites" in the already raging civil war, who achieved temporary successes against the hastily formed Red Army. There was to be no turning back, and the ruthless policy of expropriation and the "Red Terror" that soon set in - the Cheka had been established as a secret police force as late as December 1917 - during the civil war reflected this connection. Lenin's party cadres formed a community of violence and maintained a harsh regime, which they had no interest in destabilising. To a certain extent, this explains the undisputed leadership position that Lenin enjoyed beyond all internal disputes, and a sometimes almost euphoric lack of consideration. It was in this spirit that the Kronstadt sailors' uprising, which had rebelled against the Communist Party's unconditional claim to power, was crushed in 1921. The latter had long since exercised dictatorial rule.

In 1922, Lenin was already very ill when the Bolsheviks founded the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. This was partly due to an assassination attempt. What had happened?

Eckert : Lenin was seriously injured by two bullets in an assassination attempt on 30 August 1918. Fanny Kaplan was executed as the perpetrator, but without any trial. The fact that the opportunity was not utilised for a show trial may have been due to the chaos of the civil war - or even a lack of interest in uncovering the background. Lenin had made a few enemies with his blatantly illegal and undemocratic behaviour. In any case, the assassination was followed by a decree proclaiming "red mass terror". He stabilised the precarious rule of the communists, who soon prevailed in the bitterly fought civil war with millions of casualties, despite foreign interventions.

When he died in 1924, his body was embalmed and rests to this day in a mausoleum, visible to the public. Why was this personality cult important back then?

Eckert: Lenin had suffered several strokes since May 1922, and a year later he was barely able to speak. Nevertheless, and perhaps for this very reason, the unpredictable Lenin, who was surrounded by the charisma of a successful revolutionary, remained the great integrating figure of the CPSU. As long as he was alive, neither Stalin nor Trotsky dared to engage in an open power struggle, which then broke out after his death. However, both explicitly referred to "Leninism" as the binding doctrine of the party and sought to stylise themselves as Lenin's true successors. The embalming of Lenin, who can still be seen today in his mausoleum on Red Square, is one facet of a personality cult that was intended to secure power. In this context, monumental memorials were erected in large cities, but also in the countryside. Statues were erected at reservoirs and power stations, first in the Soviet Union and later in the Eastern Bloc.

What significance does it have in historiography today?

Eckert : It was not for nothing that these very statues of Lenin were toppled in many places after the end of the Soviet Union in order to deprive communism of the foundation on which it had staged its historical significance and power. The successful German film about the fall of communism, "Good Bye, Lenin!" (2003), plays with precisely this motif. Even in Russia today, Lenin has few advocates, unlike Stalin, to whom Vladimir Putin repeatedly refers. Lenin, whom he has even named as the creator of the hated Ukraine, is seen by him as a traitor to the ideal of a great Russian power. So the reception of Lenin has changed considerably after a long phase of polarisation. Communist historiography regarded Lenin as a founding hero, while others saw him as a brutal dictator who had established totalitarian rule. This antagonism has flashed up again and again since then, as Lenin's idea of a well-organised cadre party resonated strongly with other revolutionary movements; Marxist historians in the West and quite a few "68ers" also sympathised with him. Two things have long since changed fundamentally: Comparatively little research is currently being done on Lenin, Stalin's reign is receiving far more attention (apart from the fact that archival research in Russia has been impossible since the invasion of Ukraine anyway), and where research is being done on Lenin, it is now mostly done in a circumspect, hardly ideological manner.

Uwe Blass

Dr Georg Eckert studied history and philosophy in Tübingen, where he completed his doctorate with a study on the early Enlightenment around 1700 with a British focus, and habilitated in Wuppertal. Hebegan working as a research assistant in history in 2009 and now teaches as a private lecturer in modern history.